4. Zoë Berman

Studio Berman

Bristol - UK

‘Curiosity and Collectivity’

There’s multiple strands to our next guests' work. Zoë Berman operates simultaneously as an architect, educator and facilitator, alongside her role as founder of Part W.

She continues to run Studio Berman, a design practice working on a wide range of projects, predominantly across the cultural, educational, and residential sectors. These projects vary from commissions through to speculative ideas and self-initiated projects. The practice is built on a sense of community, collaboration, and curiosity. A strong network helps to form contextual and socially-rich spaces and places.

Alongside her practice, Zoë has been extensively involved in education, having worked as a design tutor at The University of Reading’s School of Architecture and unit leader at the Welsh School of Architecture. It was through the latter, under the umbrella of the schools Vertical Studio programme, that Zoë developed Rural Works, a yearly educational teaching event in Cumbria. This project has grown out of Zoë’s longstanding relationship with the rural, particularly the Lake District - where she has family connections and spends long periods of time each year. As the workshop has year on year settled into its surroundings, interactions with the local community continue to develop as the annual project unfold.

Zoë has been a strong advocate for equality across the construction industry. In 2018, she formed Part W, an action group of women working across architecture and design, infrastructure and construction - campaigning for gender parity across the built environment. Part W is a critical and urgent group that are working tirelessly to create a fair and equitable balance between men and women in the construction industry. Head over to their website to sign up for their newsletter and stay up to date on all their latest events.

Throughout the interview, you get a real sense of the subjects that are fundamental to Zoë’s practice; a heartfelt and genuine recollection of the literature that has influenced her. She covers everything from poetry and philosophy, through to books on social, political, and economic issues. There’s something for everyone in this interview…

“I might have been catching up with my reading ever since; I’m endlessly delighted by books, the joy of them, the possibility of them. The problem is I have more books than I have time.”

How many books do you currently have in your office?

I split my books between my study at home and my office, and having recently moved there are still quite a lot in boxes. I couldn’t possibly say how many I have in total! Books are a luxury that not everyone has access to and I’m immensely lucky to be able to surround myself with and try and learn new ideas from them. I really struggled with dyslexia as a child. It made me really frustrated, as my classmates started to improve their reading and I was there unable to access books in the way other people were doing. Luckily a new teacher, Miss Fischer started teaching my class when I was 7 years old. Everyone had kindly, very generously been saying that I would get there, that I was just finding my feet. But Miss Fisher came in with bright, progressive ideas – notions of dyslexia in the early 1990s would have been a bit out there, a bit ‘different’. This fantastic teacher insisted I started getting the help I badly needed. I might have been catching up with my reading ever since; I’m endlessly delighted by books, the joy of them, the possibility of them. The problem is I have more books than I have time. Or rather, I am not as good as I would like to be at making the time. Which means my ‘to read’ pile is always high, and there are endlessly things being added.

“I am not good at keeping a sense of order, not really. As anyone who sees my desk would tell you, I am more excited by doing things than I am excited about tidying up! I’d say the same for books – I am more eager to read them, than to spend time shelf arranging.”

Where do you store them, and how are they organised?

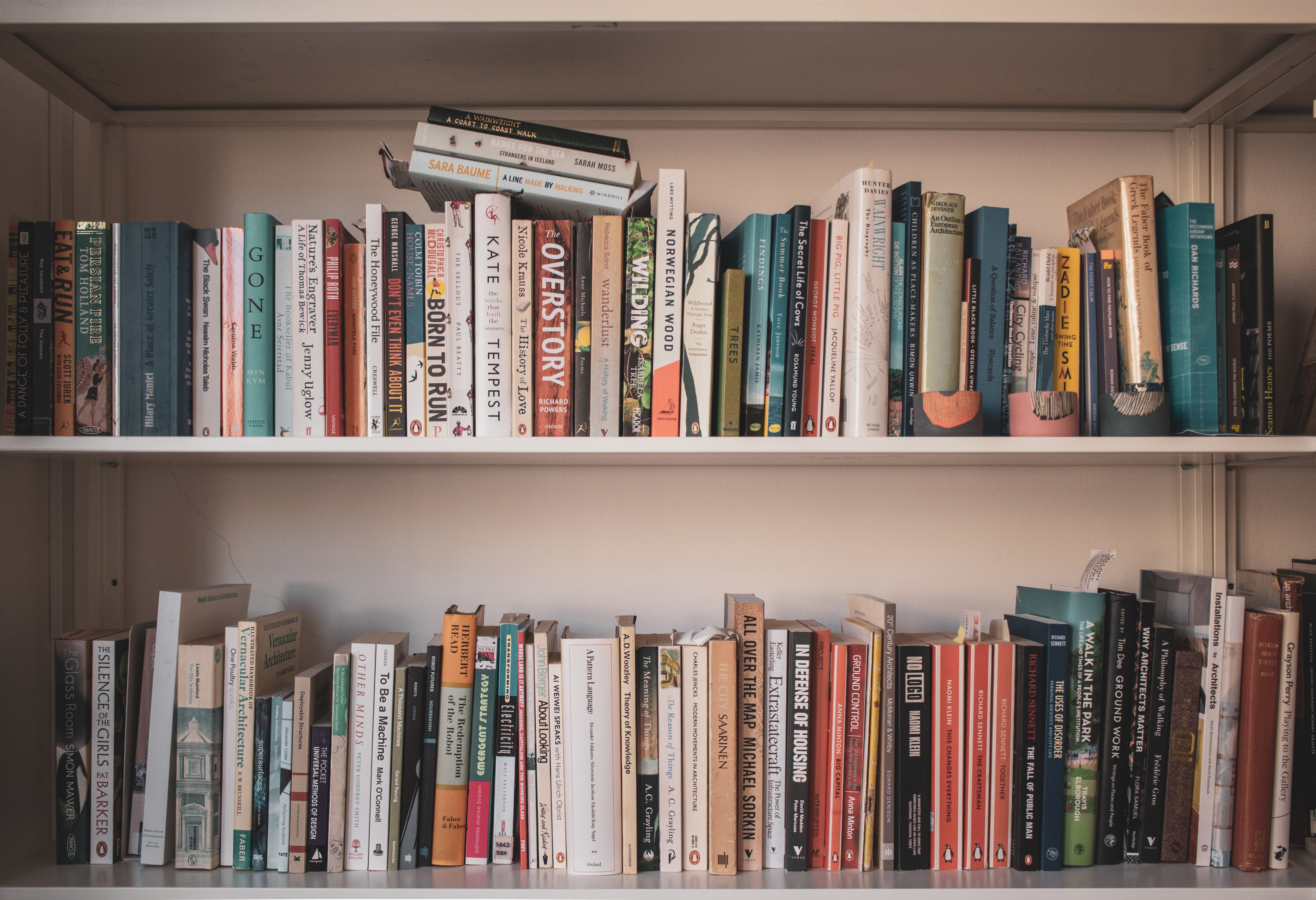

My study at home houses most of the texts I have that cover social, economic and political issues. In my office I tend to keep books that focus on design issues, to offer precedents and reference for projects we’re currently working on. There is no real order to them, though now you ask I do have my own pattern in terms of typology – shelves that house books pertaining to urban issues, for housing, sections for philosophy, a zone for poetry and so on. But I am not good at keeping a sense of order, not really. As anyone who sees my desk would tell you, I am more excited by doing things than I am excited about tidying up! I’d say the same for books – I am more eager to read them, than to spend time shelf arranging. So you’ll see a semblance of an order, say a shelf that might have a wedge of books about nature and landscape, and then that’s whoops in there comes ‘L’homme au parapluie’, the French translation of Roald Dahl’s ‘The Umbrella Man and other stories’. Or, a copy of ‘Vernacular Architecture’ by R. W. Brunskill, saved from the dead ends pile in a second hand bookshop and dogeared, and that sits along from the novel ‘The Silence of the Girls’ by Pat Barker (which I am still to read). It’s a muddle of texts. With a thin semblance of some kind of order. The stacks next to my chair at home or on my desk in the office indicate those I’m currently referring to, so there’s a sense of time and involvement associated with what is off the shelves and near me. I received a copy of 'Breaking Ground: Architecture by Women’, by Dr. Jane Hall so that is on my desk, awaiting a shelf position. We’re also thinking a lot about rural matters at the moment, in relation to the teaching work I have done with students since 2016 working on micro design ideas for a rural community in Cumbria.

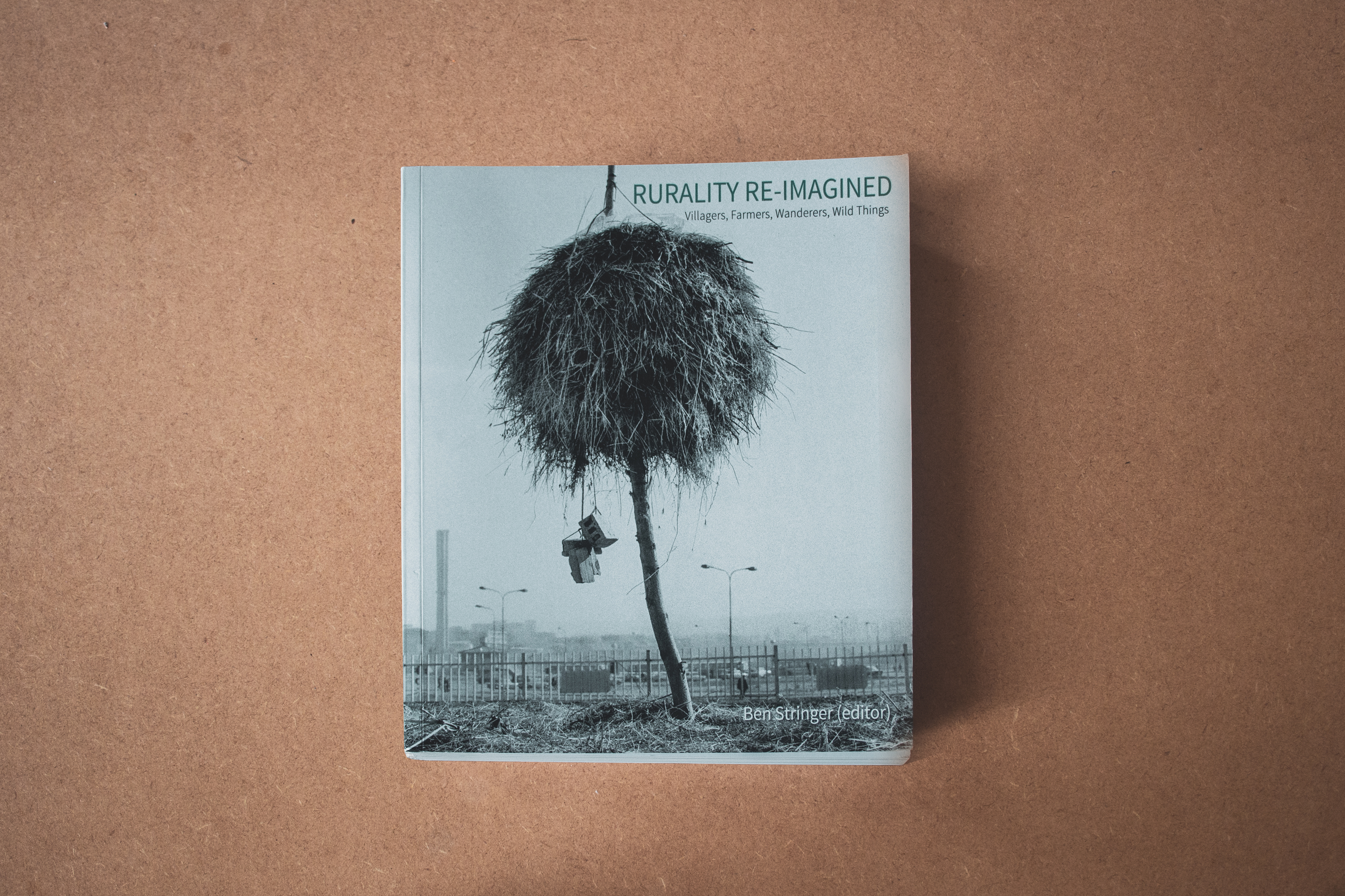

We’re working on a write-up, to disseminate the work done across five years’ worth of charrettes and conversations, and accordingly ‘Rurality Re-Imagined – Villagers, Farmers, Wanderers, Wild Things’ by Ben Stringer is near to hand and tucked underneath that is ‘Field Sketching and the Experience of Landscape’ by Janet Swailes. My dad found this in a bookshop in Kendal and enjoyed it so much he bought one for me too and it has become a real go-to for talking about drawing, observing, surveying and learning from landscape.

When I am in Cumbria, a place I have been going to since I was very young, I walk a lot – and as we’re talking about the organisation of books and their arrangement into themes, another book on my internal ‘shelf’ is ‘Wanderlust – A History of Walking’ by Rebecca Solnit.

“I think architects, and design students, need to be encouraged to think about the political issues that shape and decide our built environment – economy, government policy, social justice. Those things are shaping our lives far more than any 1:5 detail or brick specification.”

What has been the most influential book throughout your time practicing as an architect?

It changes at different moments. I’ve always been particularly interested in the potential of design to contribute towards addressing social issues. I’m not all that interested in pretty books with pretty pictures; I want books to be things I can spend time with, get stuck into. Unless it’s drawings – printed drawings, writing about drawings – that you can bury yourself in. Thinking about the books that ask sociological and ethical questions and that get me pondering, I so much admire the extraordinary work of Richard Sennett. I spent last year telling anyone who would listen about the brilliant book ‘Palaces for the People’ by Eric Klinenberg. I’ve also enjoyed ‘Massive Small’ by Kelvin Campbell and team, and to really understand the housing crisis and its root causes, everyone should read ‘Big Capitol’ by Anna Minton. I’d like to read more by Saskia Sassen. I think architects, and design students, need to be encouraged to think about the political issues that shape and decide our built environment – economy, government policy, social justice. Those things are shaping our lives far more than any 1:5 detail or brick specification. So I’ve been reading ‘The Value of Everything – Making and Taking in the Global Economy’ by Mariana Mazzucato and ‘This Changes Everything’ by Naomi Klein; but don’t test me yet, I’ve not finished them!

In 2018 I founded a group called Part W – an action group that campaigns for gender equity in the built environment and this has no doubt made me infinitely more conscious of the imbalance of most of our bookshelves – who gets published, who doesn’t, whose books are reviewed in journals, whose writings are overlooked. I’m so much more aware now of the importance of looking to both female and male writers equally, to ensure we are evolving a balanced view. I think this is right now and going forward - future tense – will continue to influence me.

“To be wholly honest, I find my ears more open to suggestions of books that come from people who work in areas other than me – in health, in tech, in publishing, in education. Their book suggestions get me outside of my field and into other areas, and I value that immensely.”

How do you work with books? Do you take notes, annotate, read aloud, draw...?

I annotate them in pencil, often use post-it note markers to indicate key chapters to return to, and write up references and quotes in accompanying notebooks. I’ll sometimes read aloud short sections to students, and share key extracts.

Where do you find the books you collect?

Written reviews on paper and bookshop browsing in person. As the founder of Part W, I’ve found it really useful to be talking to other women about their readings and it’s incredibly helpful to hear of suggested readings from my campaigning colleagues and from fellow tutors and lecturers. I like too to get recommendations for books from people who are not in the same profession as me. To be wholly honest (apologies to my professional colleagues!) I find my ears more open to suggestions of books that come from people who work in areas other than me – in health, in tech, in publishing, in education. Their book suggestions get me outside of my field and into other areas, and I value that immensely. Being taken beyond my own fences.

“We need to stop deferring only to the traditional, white-male canon as it will only ever offer us a limited view of architecture and a limited view of life experience. Our built environment needs to be supportive, kind, open to all people. So we need young architects to read accordingly – broadly, generously.”

We’re now going to need to rethink methods and routes for collecting, in all senses of the word ‘collect’. You and I first started exchanging these thoughts in the winter last year. We’re now talking during the outbreak of COVID-19. This is right now deeply shifting the way people are reading, talking, sharing information – and it’s too early to know how this is going to be in weeks, months to come. We don’t know. So right now, at this very moment I can’t go out and about to look at books hands-on. We will need to take time to digest what is happening right now, but I can’t see how the impact of this epidemic, this tragedy, isn’t going to become immensely important for us as we think about homes and housing; socialising and isolating, communality and separation. I read ‘The Lonely City’ by Olivia Laing when it was first published, which investigates loneliness, directly related to cities (in this case, New York) – explored through the work of a number of artists. This could be an apt book for us to revisit.

This question about collecting - I have just mooted an idea of Part W book club that could be held digitally. We’ll see how that pans out, but my intention is that we invite guests to suggest a chapter/ extract of a book and they guide a small discussion around that text. So that will be a new and different way to ‘find’ readings, to collect knowledge.

If you could re-discover one book, what would it be?

I’d opt for novels here, rather than traditional ideas of an architecture book. And poetry too. Poetry and fictional writing is so valuable to anyone who thinks creatively. It is such a pleasure to enjoy the imaginative skills of an author conjuring a rich senses of space and atmosphere. Fiction is such a useful way to think about people, characters and personalities. Buildings are for people, after all. Poetry – I’ll go for Anne Michael’s, ‘The Weight of Oranges’. Her writing is so richly sensorial.

What book would you recommend every young, aspiring architect to read?

Works by and about female designers, and the writings of minority groups. In teaching, we need to stop deferring only to the traditional, white-male canon as it will only ever offer us a limited view of architecture and a limited view of life experience. Our built environment needs to be supportive, kind, open to all people. So we need young architects to read accordingly – broadly, generously. We badly need design thinking that takes into account the needs of a varied, diverse population - and that needs to come through in our references, precedents and readings.

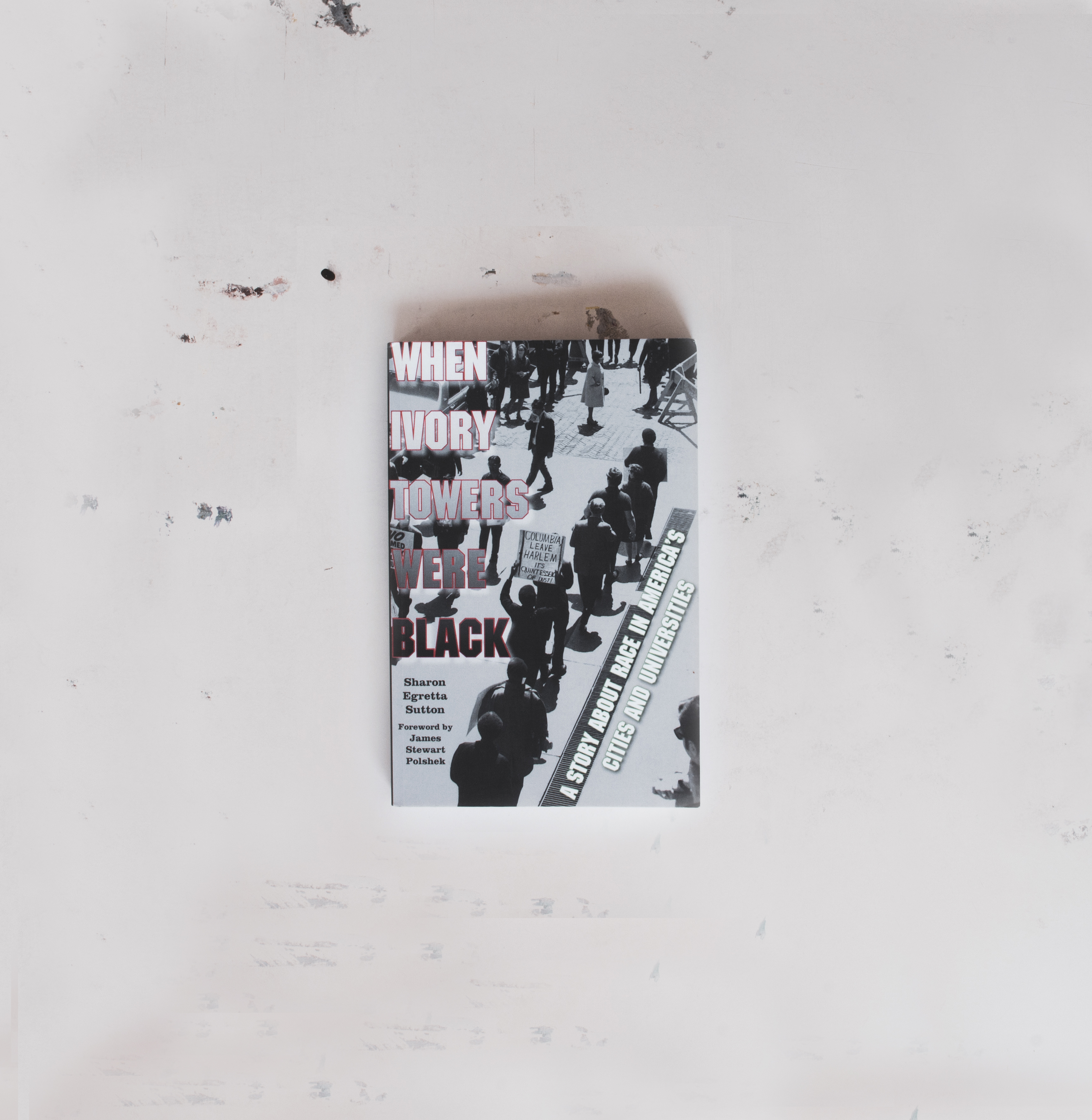

So - I’d start with suggesting the ‘Life and Death of American Cities’ by Jane Jacobs, that so brilliantly explores the value of living in cities that are rich, varied and porous. Also ‘When Ivory Towers Were Black’ by Dr. Sharon Egretta Sutton.

In gendered terms, we need to fill in the blanks - Dr. Harriet Harriss, Dean of the Pratt Institute and core member of Part W brilliantly put together a fantastic Women Write Architecture list, that is available online which I highly recommend.

I’d also suggest too ‘Hungry City’ by Carolyn Steel which so brilliantly opens up our awareness of how cities were shaped, how they came to be – and then shows us the direct and intertwined relationship between the land (agriculture and production of food) and shaping of places, and the shaping of cities (or to give a Richard Sennett flourish here, cite). Steel’s text helps remind me there is no such things as rural over there, city over here; we’re all people, moving, shifting, sharing. Needing to share. Productive landscapes and urban living are directly knotted together. The meaning of food, our need for it, our sourcing of it, food as a means for conversation, exchange and also the global versus local implications of sourcing and supply chains – that’s no doubt in the forefront of a lot of people’s mind’s right now, in this context we find ourselves in at this very moment.

I would also recommend ‘Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets and Philosophers’ by Leonard Koren. I think I discovered this when I was doing my Part I. That sounds about right. It had just been published, and I think I found it in a trendy small bookshop in Shoreditch - which I don’t think is there any more - that featured mildly obscure art books. Now of course, it’s a book that has since had a bit of a cult following. Which is kind of annoying, like when you find a small band that is playing in a local pub and 5 years later everyone is telling you about them and you feel “yeah, I know, I knew about them years ago!”. But nonetheless – trends and fads aside – I think there’s much in this book about the beauty in the imperfect, joy in error and in the organic. And it’s quite a peaceful, contemplative short book. And we could probably all do with a bit of that right now.

All photography by Tim Lucas

Website