5. Ellis Woodman

Critic and Curator

London - UK

‘Complexity and Contradiction’

A slightly different interview this time, as we talk to Ellis Woodman, an architecture critic and curator. For the past five years, Ellis has been Director of the Architecture Foundation, a self-described ‘coalition of architects, clients, professionals, and public campaigning for a better built environment’. The charity regularly hosts lectures, makes films, curates exhibitions, publishes books, and conducts study trips. Most recently, Ellis has been programming ‘The 100 Day Studio’. With two or three free online events each day, the AF has created a substantial resource. Although a fully qualified architect, Ellis gave up practising in 2003, operating in the realms of journalism and curation ever since. Previously architectural critic for the Daily Telegraph and editor of Building Design, he has also contributed extensively to the Architectural Review and the Architect’s Journal. He has contributed texts to monographic publications on the work of architects including James Gowan, OFFICE Kersten Geers and David Van Severen, Hugh Strange, Stephen Taylor, and Craig Hamilton. Most recently his text ‘Constructed Realities’, was featured in a publication on Flores & Prats’ rehabilitation of Sala Beckett.

Would you mind expanding on your extensive and varied catalogue, touching upon how you got into architectural criticism?

I gave up practising architecture in 2003 and spent the next 10 years focusing on writing and editing. During that period, I wrote for Building Design magazine. Most weeks for 10 years, I wrote a 1600 word review of a new building. I edited the magazine for a few years but it stopped printing in 2014. I then spent a year teaching and working as a freelance writer before joining the Architecture Foundation. I spend four days a week with the AF and the other day writing.

I have written about a lot of very different architects work although probably the most sustained relationship has been with Kersten Geers and David van Severen. I got to know them quite early in their independent career while curating the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2008. That year they exhibited ‘After the Party’, wrapping the Belgian Pavilion with a fence and filling it entirely with confetti. I had just published a monograph on James Gowan - rather an obscure figure then - but while wandering around this confetti-filled space on the first day of the vernissage, I met Kersten and David who were very keen to talk about the book. Kersten, in particular, has an exceptionally wide frame of architectural reference and he was very interested in Stirling’s emergence as an independent architect, that is to say the architect he became subsequent to the partnership with Gowan. Shortly after, Kersten was editing an issue of OASE on Stirling with Pier Paolo Tamburelli of Baukuh, which focused on the immediate post-Gowan period - ie between the Leicester building and the Staatsgalerie. Gowan very elegantly defines a critical difference between his architectural sensibility and Stirling’s. He identifies as a Gothic architect, whereas he sees Stirling a Classicist. Gowan’s work is always a light assembly of forms that sit loosely on the ground, organised on a quadratic grid. A typically Gothic building. Whereas, Stirling constructs symmetrical buildings, with a taut profile, that sit squarely on the ground. I think this idea of Stirling as a Classicist became very interesting to Kersten and I think it helped him identify what OFFICE was doing too.

How many books do you currently have in your office?

If you are asking about architecture books, I would estimate 1000. I’m married to a writer, so between us we have a considerable number of books. At the point of moving in together, we had to combine two libraries. My own books are predominantly about architecture and painting. I do have fiction but he reads a lot more novels than I do.

Where do you store them, and how are they organised?

Rupert’s are meticulously organised, while mine are very chaotic. Shockingly, the architecture section is almost completely ad hoc. There is a sort of British twentieth century section and a couple of shelves about the western classical tradition - architects who use mouldings. I often find that books are accumulated for a specific project. Most recently, I’ve been writing about Craig Hamilton, a South African currently residing in Wales. It’s been a fantastic project. As a critic I hope I take things as I find them but the buildings that really move me are classical and Craig is one of very few architects working in that tradition who is saying something new. The book discusses three private chapels, two mausoleums, and a bath house conceived as a temple, all built within the space of 10 years.

“I find Venturi’s ability to talk about what things look like with fantastic precision incredibly compelling.”

What has been the most influential book throughout your time practicing as an architect?

Probably the first architecture book I read - Robert Venturi’s ‘Complexity and Contradiction’. I read it when I was 17 after having seen a programme on the BBC about the National Gallery extension. I like architectural writing that takes the act of describing visual phenomena very seriously, so I find Venturi’s ability to talk about what things look like with fantastic precision incredibly compelling. My own writing is narrow in its focus. I don’t particularly write from a political perspective like Olly Wainwright, or Owen Hatherley - both writers I admire. I try to mirror the conversations that a practising architect might have in their office. A number of drawings are on the wall and you are trying to choose the best option. That’s the level of conversation I’m trying to emulate. Good criticism for me is an act of design; you imagine how a project might have been otherwise. You mentally re-design the project in your head to ascertain whether you are interested in making a critique against it. My architectural training is central to the way I write.

It’s interesting that you read ‘Complexity and Contradiction’ at a time when perhaps you weren’t even considering architecture as a career, let alone architectural writing, yet it’s the book that has had the biggest influence on you.

As a gay 17 year old, trying to work out who you are in the world, I had a very strong emotional connection to Venturi’s sensibility. I was drawn to the wit and inclusivity, the acceptance of things as they are. There’s no trace of machismo. I was very excited by Jasper Johns paintings at that age for similar reasons. You could say Venturi is to Kahn as Johns is to Rothko. That acceptance of irony was very liberating and probably still exemplifies the qualities I enjoy most in architecture.

“We’ve become very interested in this idea of the transcribed lecture. I find the format particularly compelling because of the specific relationship created between image and text. There will often be three or four images on a page, supplemented by extended captions, and a passage of text. I enjoy the act of reading and looking becoming simultaneous activities.”

How do you work with books? Do you take notes, annotate, read aloud, draw...?

Although I’m reading all the time, I’m not a fast reader. I have what some might consider a rather unappealing habit of reading in quite an instrumental way; I’m reading for things that can inform my writing. I’m actively looking for texts that can influence my own work. My reading tends to be focussed around something that I’m writing at that particular moment. As a full-time journalist, knocking out building reviews every week, I got used to writing very quickly. In turn, I developed a method of reading that aided that process. The necessity to make a living from writing has led to reading becoming a tool, it’s not entirely for pleasure.

The Architecture Foundation is beginning to publish more books. Due to the nature of the AF, we’ve become very interested in this idea of the transcribed lecture. I find the format particularly compelling because of the specific relationship created between image and text. There will often be three or four images on a page, supplemented by extended captions, and a passage of text. I enjoy the act of reading and looking becoming simultaneous activities. It’s a type of book that publishers have increasingly struggled to understand how to sell. I remember having conversations in the past with large publishing houses and it became apparent that they only understand how to sell two kinds of architecture book; they know how to sell Rowan Moore, or Tom Dyckhoff, writing a 60,000-word treatise with a collection of images in the middle; Or they understand how to sell ‘100 Modern Houses’, a high concept picture book where every picture gets a caption. It’s either all text, or all image. The transcribed lecture fills that void. We made a book called ‘Project Interrupted’, which is based on five lectures by British housing architects from our lecture programme. It was our first shot at trying to work with that format. It’s proving difficult, but we are currently trying to bring out various other lectures as individual publications. I’m hopeful the focus on housing will continue with another issue of ‘Project Interrupted’.

I’ve been reading Mark Pimlott’s ‘The Public Interior as Idea and Project’, which is based on a series of lectures conducted at Delft. I think the form of the lecture becomes apparent in the text, there’s a real directness to his language. That process of speaking to a large audience creates the requirement to speak both informatively and directly to maintain their attention. It also has that relationship between image and text that you’ve been discussing.

Yes, I’ve always greatly enjoyed Mark’s writing. I was taught by Peter St. John in the 90s, and Mark was part of that group, along with Adam Caruso, Tony Fretton…Mark was a very influential writer, perhaps the principal writer of that generation. You always got a sense that he was writing from the perspective of an artist, writing as a process of research. When I write as a journalist, I don’t necessarily have any great vision of the world. I have my enthusiasms, but I’m not quite sure how they constitute a project. When I was at BD, I had the opportunity to commission writers that I very much admired - Gavin Stamp, Paul Shepheard, Wouter Vanstiphout, Robert Harbison, Gillian Darley. In the early 2000s, Mark wrote a fantastic piece for us on Fosters’ increasing involvement in the City of London. It’s still a very powerful piece of writing.

Where do you find the books you collect?

Well I’ve run out of shelves, so it’s become a strictly one in, one out policy. It can be quite a sad occurrence when someone gives me a book. Rupert is a member of the London Library so he often goes and borrow things on my behalf. I’m currently starting on what I hope will be the longest thing I have written - a book about Austen St. Barbe Harrison, an early 20th Century architect, who built quite extensively across North Africa and the Near-East. As a result, there’s currently a lot of literature from British authors of that period in the house. The Internet Archive is also a fantastic resource. An amazing website that has a huge library of downloadable material, all for free. It’s beyond belief. It’s like google books, but infinitely broader! Certainly most books pre-1970 are available. It has numerous back issues of the Architectural Review. That’s really put a dampener on my expenditure on books.

“Stamp wrote one of my favourite books, perhaps the best book ever on a single building. It’s only 30,000 words, but Gavin takes the stance that this is the greatest building, by the greatest British architect of the 20th Century. You really believe that by the end.”

If you could re-discover one book, what would it be?

I think ‘Architecture of Humanism’ by Geoffrey Scott, which Craig Hamilton suggested I read around 7 or 8 years ago. I suspect I would understand the text better now having spent a lot of time looking at early 20th Century classicism in the years since. Craig was very close with Gavin Stamp, who wrote one of my favourite books, perhaps the best book ever on a single building, Lutyens’ ‘Memorial to the Missing of the Somme’. It’s only 30,000 words, but Gavin takes the stance that this is the greatest building, by the greatest British architect of the 20th Century. You really believe that by the end. Gavin had an incredibly vast frame of reference and introduced Craig to a lot of unfashionable Edwardian English architects, like Arthur Beresford Pite, Giles Gilbert Scott, and Albert Richardson. These references became very significant for Craig, helping to define who he was as a Classical architect. He had no interest in becoming an 18th Century Revivalist, but rather wanted to define his own language within the Classical style and I think he’s achieved that. Through Craig, I became aware of many architects of that generation who I had never taken seriously before… ‘The Architecture of Humanism’ argued for the relevance of the architecture of the Renaissance at a time when English architecture was very much dominated by the Gothic Revival. It triggered a very widespread re-engagement with the Classical tradition that extended into the 1930’s.

What book would you recommend every young, aspiring architect to read?

I’m going to choose two very different books. First is Osbert Lancaster’s ‘Pillar to Post’, first published in 1939, which is a very funny single volume history of architecture. He was a cartoonist and writer of real genius. He creates these fantastic terms, such as ‘Stock Broker’s Tudor’, the ‘Aldwych Farcical’, the ‘even more functional’. The categorisations are incredibly witty and precise.

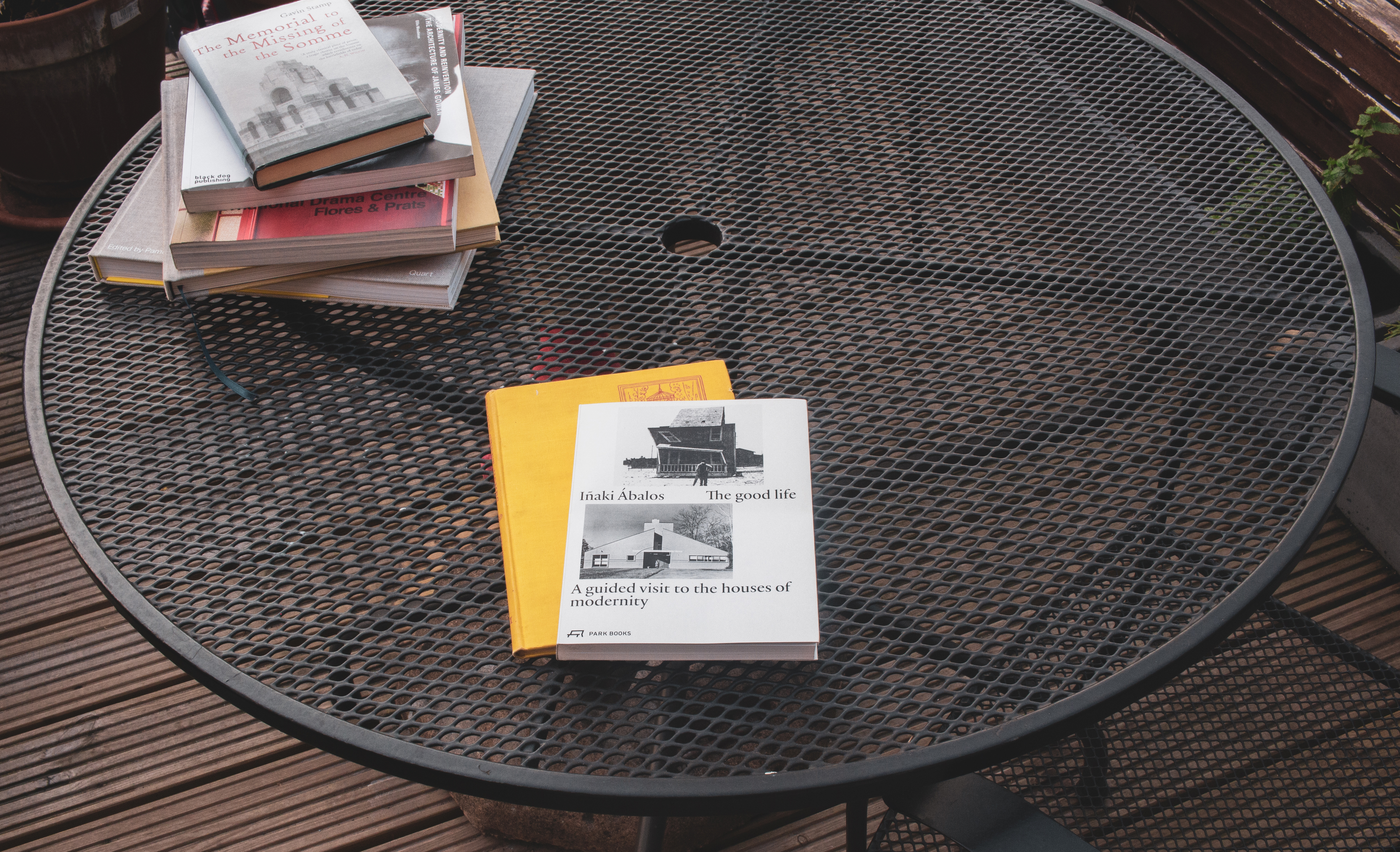

The other is Iñaki Abalos’ ‘The Good Life’, which I think is the best and certainly the most influential piece of architectural writing published this century. As previously discussed, a lot of my favourite books are transcribed lectures - ‘Complexity and Contradiction’, Summerson’s ‘Language of Classical Architecture’ - and ‘The Good Life’ is another one. I was introduced to it by Florian Beigel who was a great fan. Each chapter is a description of a different kind of modern house, such as Jacques Tati’s house from ‘Mononcle, Heidegger’s cabin in the Black Forest, or the New York loft of Andy Warhol. Each house represents a different concept for living and Abalos asks, what kind of city, or collective identity, can you make from them?

All photography by Tim Lucas

Website