4. Nana Biamah-Ofosu

Architect, Educator, Researcher

London - UK

‘Continuity, Utility and Change’

Our next guest Nana Biamah-Ofosu is a Ghanaian-British architect. She is the director of YAA Projects, an architecture, design and research practice dedicated to exploring counter-histories, material and diasporic culture, through making, speaking and writing architecture. Recent projects include Althea McNish: Colour is Mine, which was included in The Guardian’s ‘Best Designs and Designers of 2023’, the ArchiAfrika Pavilion and Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the 18th Venice Biennale which was selected as part of ArchDaily’s ‘Top 2023 Pavilions and Installations Interrogating Architecture of the Global South.’

As part of the Curator’s research team at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, Nana contributed to the articulation of the main exhibition and Pinpoint, an archive of African and African Diaspora practitioners focused on decarbonisation and decolonisation.

Nana has lectured in U.K and internationally, including at the inaugural Venice Biennale College Architettura, Kingston University and currently at the Architectural Association where she leads a diploma unit. Her practice explores African modernity and its architecture and urbanism, communality, domesticity, identity and geography through a diasporic and decolonial framework. She has been researching African compound housing as a building, spatial and material typology which can inform the development of future housing and urbanisms with a book due for publication later this year. YAA Projects recently presented Common, Communal, Community an exhibition in Vienna showcasing evolving this research.

Nana has served on the juries of several awards including the RIBA Silver Medal Jury. She is a member of the RIBA Awards Working Group and Soane Medal Committee. Her writing practice explores the social, political, and cultural impact of design and architecture and engages with leading practitioners in contemporary practice, defining a critical, expansive, and open discourse on the built environment.

I remember being an incessant reader as a child. On Saturday mornings, my dad would take my brother, sister and I to the local library. It became a ritual for me. You don’t have to own every book to enjoy every book. The loss of the library to students over lockdown must be devastating; that joy of going to the library to discover things is being missed. You often go for one thing but find something completely different.

It definitely doesn’t have the same feeling, scrolling through the database.

Reading online is very different to reading a book; you miss the opportunity to just open a page at random, out of curiosity. Instead, on screen, it takes constant scrolling meaning there is very little room for chance encounter and discovery. I currently have a folder on my computer called ‘To Read’, the ghost of all the essays that I promised myself I would read. You find one paper and it leads you to another and the reading list grows and grows. I’m interested in how reading has changed for a lot of people - it has become a lot more digital. Should there be such a distinction between the books on your shelves and the books on your computer? One thing I discovered whilst preparing for this is that a lot of the books that have been seminal for me, I don’t own! I think the relationship between books when you are a student and when you are a practitioner is fascinating.

One of the questions you set out was ‘how do you work with books’ which got me thinking about all the books I don’t own but have enjoyed reading. There’s a box of photocopied PDFs at my Mum’s, gathered through my education. I always enjoyed this way of working with books; in some ways I could be less precious about marking them and this feels to me like a very immediate way of reading. I continuously go back to the bibliography of both my undergraduate and postgraduate dissertations, a personalised, intuitive version of the university catalogue that has been created just for my own interests.

It is quite a personal view.

Most definitely. They all represent choices; who you cite; who you choose to read; and who you then include, they are all choices that you make. That has always been interesting to me.

Do you feel like there is a hierarchy to the sources you think about personally, or something that you have noticed during this process? Where do you see journals situated, for instance?

I must say journals haven’t come up a lot. OASE journal has been referenced a couple of times, but other than that, they haven’t really been discussed. I think that is a commentary on how people are consuming journals. Like you were saying, people are more likely looking at them online, which means they are less likely to talk about them on a platform such as Arch-ive. They may well be reading the Architectural Review long read, but they are doing it on their phone, or on the tube perhaps, rather than in the printed magazine.

Journals were a great source of information and reference in writing my dissertations. For me, they are as legitimate as books. Anything written holds weight. I would be lying if I didn’t say that I prefer a book to reading on a screen, but there is something about the vast knowledge to be found in journals.

I think there is a real immediacy to journals. You know that someone has come up with an idea, they have researched it and written 2000 words about it, a very focused portion of time. A bit like the article you wrote on Peckham.

I enjoyed writing that piece. I’ve never lived in Peckham but I’ve always been fond of it as it has always felt like an epicentre to Ghanaian communal life. When my parents came here in 2000, they lived in Peckham, as did many new arrivals. There’s a shop called Kumasi Market, named after Ghana’s second largest city; a microcosm in which there is a shared heritage. They are 6000 miles apart, but it still has the same energy and intensity.

In 2019 with Studio 2.2, the architectural design studio I teach at Kingston, we did a mini-project in Peckham before we went to Ghana. When we got to Accra, many of the students were remarking how similar it felt to Peckham. I thought that was really interesting, this transposition of one place onto another. Of course, you will never get this ‘stamp’ whereby it becomes the same. However, different things merging has really interesting outcomes. A Georgian street can host the life of ‘other’ people and the things that they need. That act of translation has always been something that has fascinated me. I guess this stems from feeling like I didn’t quite belong for a long time. I was born in Ghana and lived there until I was ten years old. The strong connection I have to Ghana has been developed over time. In my teen and young adult years, it felt strange to visit and be recognised as a visitor rather than a Ghanaian. Yet, when I was in the UK, I didn’t necessarily also feel British. You are Ghanaian, you have the birth certificate and heritage to prove it, but there is a detachment from the people that live there. At the same time, you are not quite British enough. This idea of translating one’s being is a very diasporic condition. I guess that is why I’m really attracted to places that embody that; how do you claim your own within a territory?

I really enjoyed a TED talk by the writer Taiye Selasi, ‘Don’t ask me where I’m from, ask me where I’m local’. It is incredible. She talks brilliantly about this diasporic condition; being split between places and how the question ‘where are you from?’ demands a scientific, sanitised and sometimes oversimplified answer that cannot capture the complexities of identity and belonging. You don’t necessarily have to be of the diaspora to understand this. Being local to somewhere feels truer to a person’s identity and that act of translation becomes part of how people inhabit their local; it encapsulates what they bring with them, what they know.

It is interesting that the Georgian terrace becomes a background for this; a framework for people’s energy that goes beyond the place. This small portion of Ghana, in the UK, that to you feels truly similar to Ghana in many ways, is amazing!

It is, and you find the same if you look at other areas of London, particularly in the South. Peckham, Deptford, Brixton, all have quite specific connections to the African and Caribbean diaspora which I would love to trace. The article on Peckham is unfinished, it is the beginning of a story for me. There is definitely more I want to write.

Was there any literature that fed into that piece?

I read a lot of fiction, perhaps strangely for an architect. That piece was indebted to a culture of psycogeographical writing particularly focussed on Black immigration. My sister first introduced me to Sam Selvon’s ‘The Lonely Londoners’, written in 1956 about a Trinidadian man, living in West London. This book offered common ground between us, she a writer and I an architect. It made me realise how important storytelling has been to my education. Literature and the role of fiction and narrative feels very relevant to me in the training of an architect. It introduces you to the narrative of places and helps you to understand them better.

Selvon talks about a man arriving in London, who is met by another man in Waterloo Station. It is such a typical immigrant experience; to be met by someone, potentially a family member or a friend, or even a friend of a friend. This person becomes somewhat of a city interpreter, helping you to find your feet in the otherwise quite impenetrable new place. This book felt like it could have been written in 2021. Talking to older relatives who migrated, the experience described by Selvon in 1956 felt as true to them when they migrated in the 1990s and 2000s. I find that fascinating. It is the same condition. It reminds me of a paper, ‘People as Infrastructure’ but AbdouMaliq Simone, a really beautiful text looking at African cities and the way that people act as infrastructure and connect places and spaces. He describes this scene, where he is in a bus park, watching the bus boys, drivers and passengers working together like a silent choreography. There is no instruction, but everyone knows where they need to be and what they are doing. This a local infrastructure that people have built with architecture and the built environment as background.

Much like Ballard, but a positive codified experience rather than this dystopian future.

And how are you working with books? Are you taking notes..?

Well, the journals are scribbled all over.

And what about novels? Are you picking out specific quotes like you did for your piece for the Architects’ Journal on ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’?

‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ taught me so much about architecture and how to relate to it, especially African architecture. Adichie is writing about the Nigerian-Biafran war in the 1960s. Nigeria was amalgamated by the British in 1914. So, before that, it was divided by the River Niger. They had different customs and ways of living. As such, this unification was problematic. A troubling pre-independence election and a series of military coups led to the South-eastern territory seeking to become its own country, Biafra. An estimated two million people died in the war that followed, in which the Nigerian State was supported by the British Government who sought to protect its amalgamation. I was 21 years old when I learnt about the Nigerian-Biafran war – my education had skipped this major historic tragedy and that made me think: ‘what else I didn’t know about the part of the world I am from?’ It sparked everything that I am thinking about in my work now. I had questions; what were these countries like before colonisation or at the dawn of independence?; What was their condition?; How did people live?; How did they build?; What was their architecture?; What was their place like?

When I wrote the piece for the Architects’ Journal, I re-read the novel and was again struck by Adichie’s descriptions of places. She talks about the lead characters, Olanna and Odenigbo and their lives on Nsukka University’s campus; the red earth of Nsukka and the modernist bungalows set against beautiful landscapes. You start to build an intensely rich imagery; vivid scenes of tropical modernism that Adichie describes so well. The other place she describes is Kainene’s house in Port Harcourt,

“Kainene

picked him up from the train station in her Peugeot 404 and drove away from the

centre of Port Harcourt

towards the ocean to an isolated three-storey house with verandas, wretched in

creeping bougainvillea

of the palest shade of violet. Richard smelt the saltiness of the air and

Kainene led him through the

wide rooms with tastefully mismatched furniture, wood carvings, muted

paintings, landscapes and rounded

sculptures. The floors polished had a wooden scent.”

You can really visualise the interiors. Those are the kind of imaginations that I want to work with. But these have been abandoned in places like Accra (where I was born and partly grew up) in favour of interiors that are often sterile, influenced by the West and the colonial hangovers that have dictated what people attribute to being modern. In ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ Adichie presents a language and character of an indigenous architecture. It holds a rich collection of places and people’s memories of those places, which I find remarkable.

Other scenes are set in the central courtyard space of a multi-generational/family house, typical of traditional African architecture. It is where communal living happens, where inter-personal relationships are developed.

I am very interested in this idea beyond the building; what are the stories these buildings hold? How are they used? ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ is not an architecture book, but it is a book that centres architecture, space and territory in its exploration of the human condition. It is an important book for me.

Following that, I read Chinua Achebe’s ‘There was a Country’. Achebe’s personal history of Biafra; a biographical, place-based text weaving together poems and prose. A beautiful narrative that is situated so distinctly in a single place, perhaps made more pertinent by the fact that it is a place that no longer exists. The images you form are so sharp in your mind. Both of these have been seminal books for me.

With your work at Kingston, are you using these texts? Are students largely reading narrative-based texts or have you found that there is also an architectural set of literature that you are also promoting?

We do both. In the studio, we believe that reading is an important part of an architect’s training. This tradition developed with the late and dearly missed, Mary Vaughan Johnson, who was a brilliant scholar who very much used books to open up a conversation, to allow students alike to bring a personal reading of architecture and space with them Reading is central. If you are not reading as part of a studio culture, then you are essentially educating architects based on aesthetics only, You are educating architects who don’t have reasoning for things. We regularly have reading seminars in design studio. We feel that space needs to be made for students to actuallyread and discuss the books on the reading list. Students are busy and stressed and they need time. Not everyone knows how to read in a way that can become useful for them. For some people, reading in a silo is not that engaging, and this is where being able to talk about what they are reading in relation to their design thesis work becomes critical.

I think that is fantastic. But also really important that as a student you would be able to recognise the importance placed on reading by your tutor. It makes you understand that the tutor has read it and that it is important to them. At university, it can often feel like the reading list gets regurgitated from the year before. They probably haven’t been read or thought about by some tutors for some time.

I still have a collection of books that I bought when I first started university. Being particularly keen, I bought every book on the list. Some of them have been great and are well used, like Deplazes’ ‘Constructing Architecture: Materials, Processes, Structures’ -an immensely rich book on building culture. I think as an educator, it is also important to share the reasons behind why you promote certain books to students - I am recalling some of books on my first year reading list, which although seminal and important felt very distant for someone new to architecture. Other books, like ‘The Dictionary of Architecture’, as interesting as it is, I haven’t referred to much. I have grown to understand the importance and significance of Kenneth Frampton’s ‘Modern Architecture: A Critical History’ but reading it as a first year without the proper forum or framework for discussion, made it quite inaccessible at the time.

Exactly. I also bought ‘Modern Architecture’ in first year. It does make you question what first year student is going to read a 2000-word essay on Mies van der Rohe and be blown away? Whereas actually, giving students ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’, or passages of it that students can relate to and think about in a critical way, could potentially be a more successful route to thinking about architecture.

One book I enjoy reading was Jun'ichirō Tanizaki’s ‘In Praise of Shadows’. Like you said, it is almost not about architecture, but rather everyday things. “While the texture of Chinese paper and Japanese paper gives us a certain feeling of warmth, of calm and repose.” Then there’s some notes in here written by 19-year old me, “The importance of surface relating to Robert Ryman...” I then ask a question, “What has this meant for my work? Note. How have I selected certain papers for making drawings?” It is really interesting to see those connections now; being able to pick this up and glimpse questions I was asking as a student is a gift. Everyone understands a book like ‘In Praise of Shadows’, it is about the objects and spaces that support the ordinary. Everyone can form a connection to it through their own experiences - of things that they have held and things they already know. It is a book that made me realise architecture was about everyday things..

In my teaching practice, last year with the late Mary Vaughan Johnson, Michael Badu and Bushra Mohamed, we used seminal texts to support design briefs. A brief which asked students to consider the individual dwelling within an urban housing design programme, was paired with Joseph Rykwert’s essay on the house, talking about its origins and symbols and Rudofsky’s work on hygiene, ‘Now I Lay Me Down To Eat.’ We coupled these readings with the design of unit types in order to get students thinking about daily habits and rituals; to design spaces within the home that enable these activities and to move away from the numerical and data driven approach to designing housing that fails to consider the lives of the building’s inhabitants. After all, that is what a house is, a place that enables ritual, daily activity and custom.

Our readings from Rudofsky’s ‘Now I Lay Me Down To Eat’ focussed on the chapter, ‘Hygiene as discount’ and Mary as a scholar on the subject of hygiene led a reading seminar on the topic in studio. I remember an important moment during this seminar when a: a British-Beninese student, whose family are from Benin, spoke about the strangeness of the western flush toilet because as a child she had experiences using the squat toilet as was popular in her culture. I loved that. I loved that we had created the kind of open, curious and safe learning environment where a second-year student felt comfortable to talk about her own cultural experience of space and ritual, one that went against the normative western experience. We also read a transcript of a lecture given by Louis Kahn, called ‘The Room, The Street and Human Agreement’ where he talks about the room as the foundational element of architecture. He starts,

“I

have some thoughts on the spirit of architecture. I have chosen to talk about

the room, the street and the human

agreement. The room is the beginning of architecture. It is a place of mind.

You in the room with its dimensions,

its structure, its light respond to its character, its spiritual aura,

recognising that whatever the human

proposes and makes becomes a life.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Reading Kahn’s transcribed lecture as part of Studio 2.2 and then looking at this book, ‘The Houses of Louis Kahn’, helped me to see Kahn’s work in a different way. His houses are phenomenal. My fifth-year thesis questioned whether there was a difference between making a house in the city and a house at the edge of a city. I remember a conversation with Philip Christou and Hugh Strange in a crit where we talked about the difference between a house, and housing. It made me realise that the fundamental aspect of good housing is a good house.

We also read ‘Continuity, Utility and Change: The Urban Compound House in Ghana’by Professor Samuel Owusu Afram from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Ghana (KNUST).There is very little writing on this topic, which is something we are looking to address as part of our research project and to present it in a comprehensive manner. This book has been particularly pertinent for Bushra (Mohamed) and I, ‘Construction Technology for a Tropical Developing Country’. It is a survey of Ghanaian architecture, published in 1983 by Hannah Schreckenbach and Jackson G.K Abankwa, both of whom taught at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Ghana. It contains a series of surveys undertaken by architecture students and is a seminal book on Ghana’s architecture. It has an incredible collection of hand-drawings describing how buildings are made and the particular nature of a Ghanaian architecture. It is very matter of fact, it is about building, and building technology, but it is also poetic in as far as it is about people’s attitude to building. I feel very lucky to own this book now, especially with such a strong desire to learn more about Ghana’s and in general Africa’s traditional building cultures.

Similar to the Deplazes book in a way.

Exactly. This book is a snapshot of a specific time in Ghana. My ambition is to re-catalogue this now. We see our research as a five-year long project and we are keen to visit and study as many African countries as possible, to see how they deal with the compound house..

Another set of books worth referencing are W.B Mckay’s ‘Building Construction’. I got these for a second-year technical assignment called ‘The Naming of Things’ for which we were asked to produce detail drawings of our home. The house I studied was my childhood home in Milton Keynes, a typical suburban home. These books were a wealth of knowledge, describing building construction in a simple and visually coherent way. I am very lucky to have the full set of the 4th edition, given to me by Dad, who bought them as a student himself as a Building Technology student at KNUST. I also love that this book was once sold at £2.00!

One of my recent purchases is ‘New Directions in African Architecture’. It is part of a series, with each book focusing on a different place, ‘New Directions in American, German, Italian’ and so on. They are just beautiful. The book presents an overview of Africa’s tropical modernist period with some interesting building studies.

I think those kinds of series are fantastic; a set of books that investigate various countries. It offers a real insight into one country, a depth to that specific study, whilst the series itself enables comparison.

The final collection I want to talk about are very dear to me as they belonged to Mary. Her children invited us to have some books that belonged to her. ‘Lived-in Architecture: Le Corbusier's Pessac Revisited’ by Philippe Boudon and Gerald Onn was an important text in framing our studio agenda last year. It covers the story of lives lived in Le Corbusier’s first housing project at Pessac near Bordeaux. It is a book that examines the violence of an architecture that is based only on its author’s assumptions. This book covers the changes that residents made to the scheme to reflect how they actually lived and who is to say they are worse off after these additions? They are lived in, in a way that people find useful. That really makes me question the role of the architect in determining the essence of home and as an architect, working in housing, especially lucky to work for a practice interesting in social housing and regeneration, these are ongoing preoccupations. I also have two copies of ‘The South African Journal of Art History’ from Mary One of my last encounters with her, she delivered a lecture to my diploma unit at the Architectural Association titled the ‘The Temporality of Toilet Rooms of the Maison de Verre’ which is also presented in Volume 31, no. 2 of this journal in 2016. It was an incredibly rich lecture which detailed the development of hygiene and the flush toilet in Europe. The lecture and paper were based on Mary’s experience of Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre in Paris, where she was the Chief Docent and Curator for nine years. In the lecture she gave, and the paper published in ‘The South African Journal of Art History’, she explored the influence of modernity and modern science on architecture and notions of hygiene. Mary argued that it is the most codified space in the house, yet it also links us all, in so many different ways. We all use it, but it also forms part of a network that connects us - the individual toilet becomes part of a network of infrastructure in the city. It is a rich and beautiful essay.

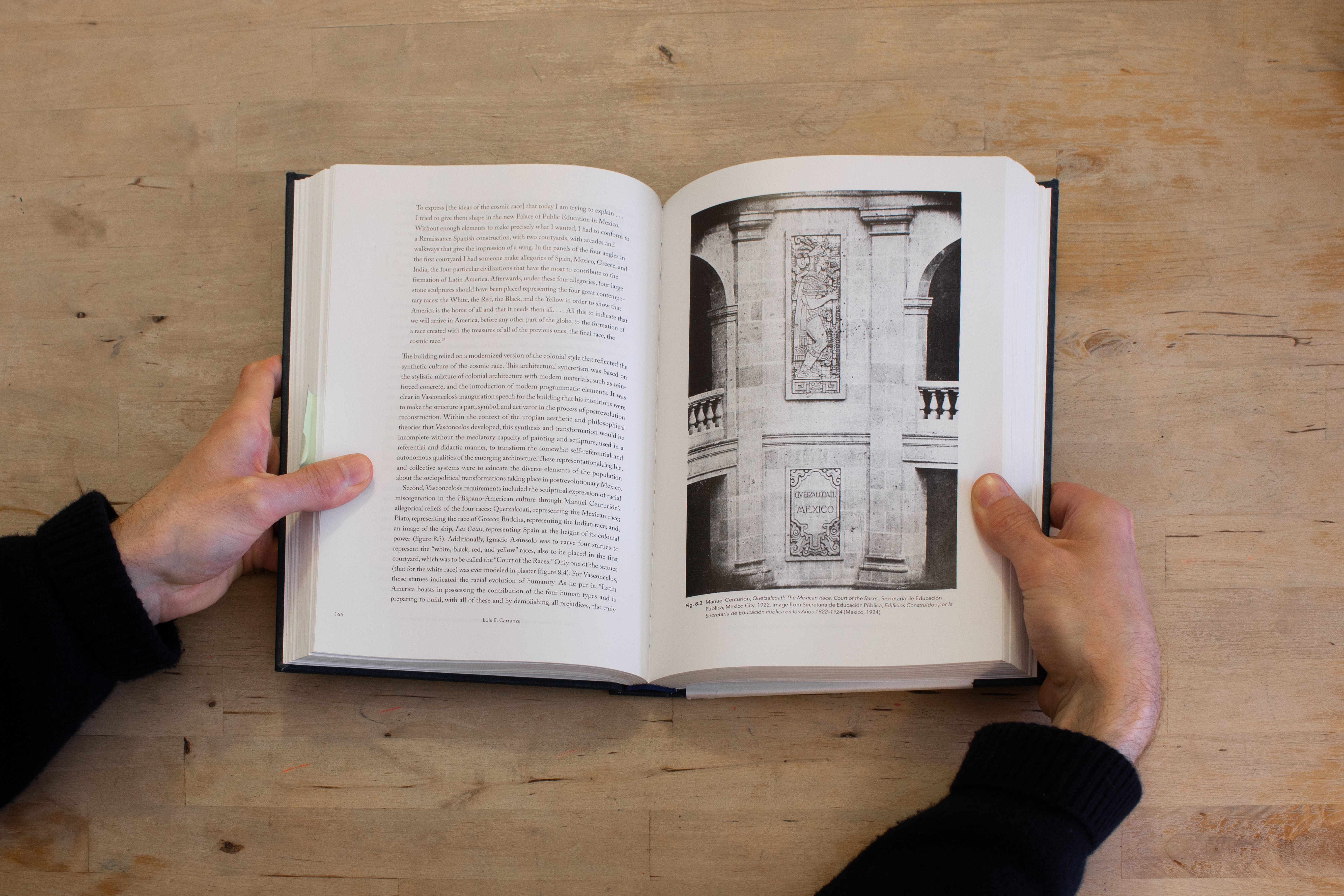

The last book in this collection is ‘Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present’ by Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis and Mabel O. Wilson. I reviewed it last year for the RIAS Journal when it was released in the UK. It is the book I needed when I was studying and becoming interested in the intersections of race and architecture. It is a seminal book and it should be elevated as such to the status it deserves. For a long time, I and many other who were interested in this intersection were made to feel as though these two topics were separate, that architecture was ‘above’ all else. This book reveals their deeply rooted connections and highlights the notion that architecture is a reproduction of our social commentary and that you cannot separate these things.

I loved your quote, ‘Architecture is about imagination; A building is the physical manifestation of a people and their aspirations.” I thought that was amazing and feeds into what you are talking about here.

Yes. Mabel O. Wilson talks about the US Capitol building, but rather than just talk about the architecture, she also discusses who is building it. If we are talking about a building dedicated to a state supposedly built on freedom, then the slave labour behind its building has to form part of that discussion. It completely changes the way you read it. Architecture often tries to sanitise these elements. The actual building is only half the story.

The other essay I really enjoyed in this book was, ‘Race, Architecture and Colonial Crisis in Kenya and London’, Mark Crinson’s essay on the way architecture was used as a violent colonial tool to organise and re-shape people’s living conditions and to make certain areas more policeable. Crinson analyses that in an interesting way, discussing the Gĩkũyũ people’s culture focusing on building as community, both spiritual and ritual. Kenya’s architecture and urbanisation, like that of most African states, was formulaic to advance the cause of colonisation. It is an important book and one I’ll be referring to for years to come. The introduction, for instance, covers an important topic that is central to the work Bushra and I are undertaking; that Black and African culture can be philosophised about as a building culture and used to help people to understand their own tradition of living. The western framework for research is not always suitable for looking at other people’s histories or cultures as it rarely looks beyond building and artefact. This is why I particularly enjoyed Wilson’s writing on the Capitol; she places emphasis on Jefferson’s personal records; the slaves he owned whose labour was used to construct a building in celebration of freedom. All of these factors and details add to the story of the building and the subsequent research, yet the western canon excludes this methodology – of looking beyond the building - from its approach to critiquing architecture, much to its own detriment. We need to critique architectural history with reference to race, to interrogate the ways in which historians have discussed the conditions and circumstances around particular buildings, and to recognise the role and influence of our social histories on architecture from the Enlightenment, all the way to Modernity; there is no part of history that is untouched by race.

All photography by Tim Lucas unless otherwise stated.