8. ii) Níall McLaughlin

Architect

London - UK

‘Shem and Shaun’

This is a transcript of a discussion held between Níall McLaughlin and Arch-ive, as part of the Architecture Foundation’s ‘100 Day Studio’. Part ii looks at 3 of Níall’s early projects, The Shack, a private house in Wandsworth and Phototropic. The full interview is available to watch here.

(1) The Shack

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

During our preparatory sessions, we touched briefly on three projects from the beginning of your career. I think it would be interesting to discuss those and how your perception has changed and whether the influence of literature has altered this perception at all. I think the three projects, The Shack, a private house in Wandsworth, and Phototropic are all from the 90s...?

Correct. Yes, they’re all from the early 90s. I was 28 at the time and had just opened my own practice. It was an interesting time. All of these projects were undertaken for the same client, a photographer, Gina Glover. She produced these beautiful photographs about chromosomes for a hospital in London, incredibly inventive photography. It was for a fertility hospital and she just took simple pairs of socks and photographed them together. As a client she was completely open to the idea of an architect and what they might do. She was very creative, but she had no sense that what you were doing was taking anything away from her, instead she was able to participate in your creative process in a really ingenious and interesting way. It opened up a lot of opportunities for me as a young practitioner.

(2) John Cage’s ‘Fontana Mix’ and (3) Tarkovsky’s ‘The Stalker’

[Images courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

[Images courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

I’ll start by discussing the tiny patio we did at her house in South London. (2) I had just discovered John Cage’s ‘Fontana Mix’ drawing where he was making open scores. He specified certain points around which he opened up the piece to improvisation. I wondered whether working drawings or instructions for builders could have the same kind of quality - to allow for improvisation and chance, for things to emerge outside of the architect’s own authorship. I designed a very simple window looking onto the patio, which I specified down to the last detail myself. I did entirely comprehensive working drawings. In contrast, I asked a group of makers to come together and develop the paving through improvised interpretation of an open ‘score’ that I created. The work was opened up to other people, to make, but also to design and create through making.

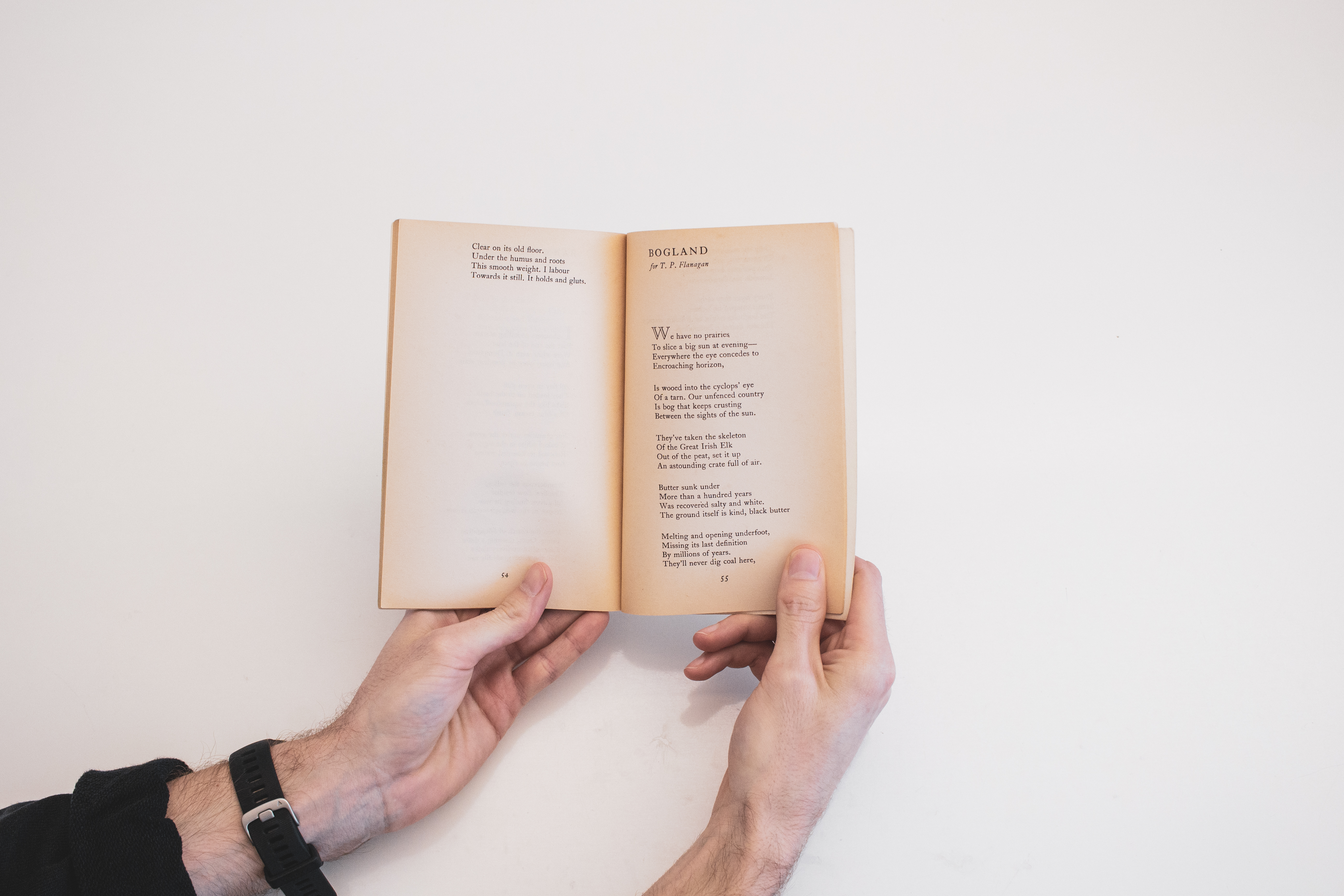

(4) ‘Door into the Dark’ / Seamus Heaney (Faber & Faber, 1968)

“We thought of the paving as a facade for the ground, both concealing what is below, but also representing it. In that way, the surface becomes a screen for representation.”

“We thought of the paving as a facade for the ground, both concealing what is below, but also representing it. In that way, the surface becomes a screen for representation.”

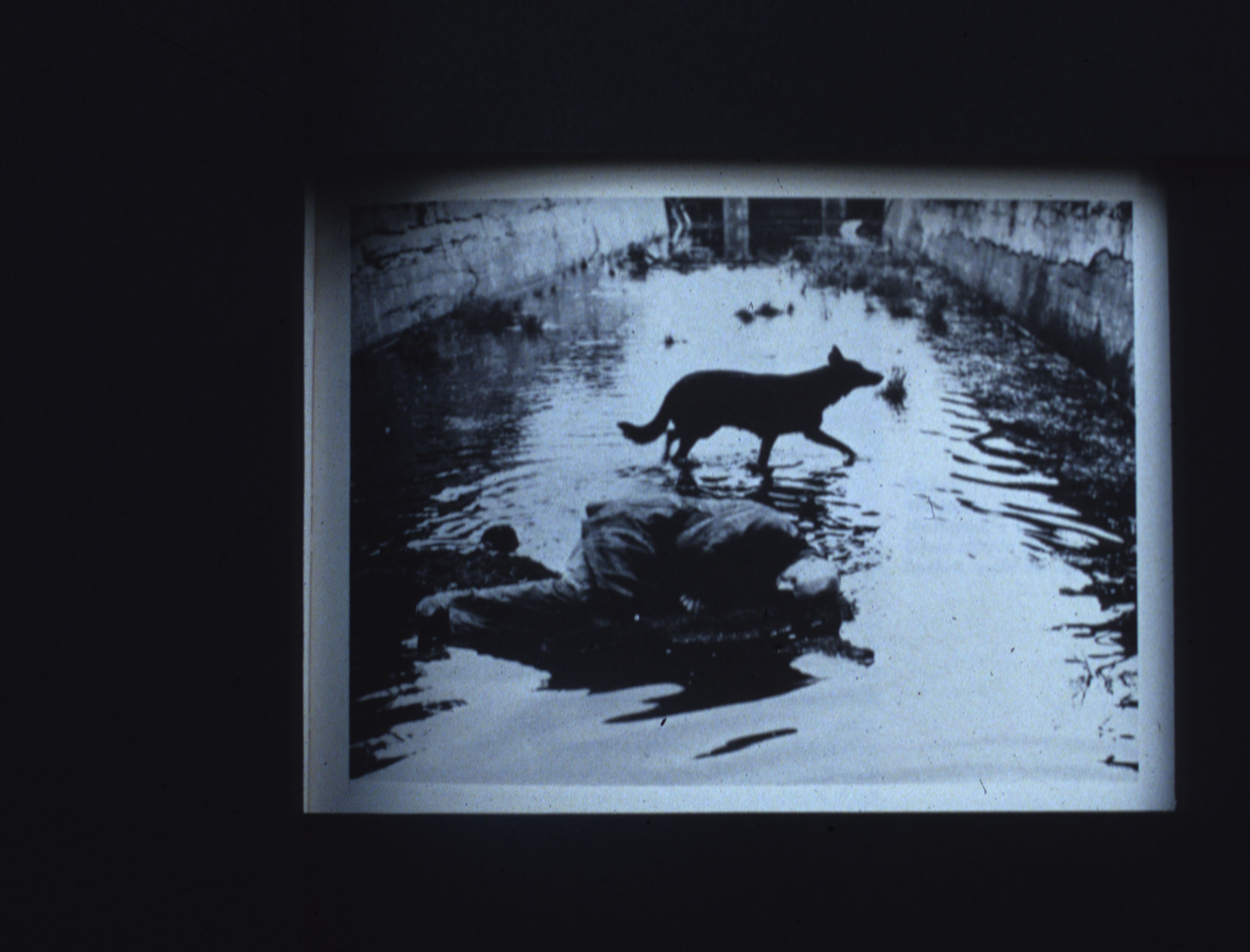

Many of my prompts were concerned with the relationship between surface and depth in relation to the ground. (4) Seamus Heaney has a wonderful poem called ‘Bogland’ where he talks about the bogland as if it were a communal unconscious. Things get dropped into the bog and stored, only to be found intact hundreds of years later. He sees them as being concealed, but also passed into the future - the idea of the ground as being unconscious, yet both creative and fertile. It touches on that idea of loam once again. We thought of the paving as a facade for the ground, both concealing what is below, but also representing it. In that way, the surface becomes a screen for representation. (3) Another reference was ‘The Stalker’ by Tarkovsky, the movie every architecture tutor in the world has shown their students. There is a scene where he’s lying on the surface of the water and, seen obliquely, it’s an entirely reflective element. As the camera pans up, you look down into the water and see this detritus of icons, coins, syringes, guns...All lying at the bottom of this water. It speaks of the relationship between surface and depth that is alluded to in these images. We gave a number of these queues to the builders and asked them to make the pavement on that basis. (5) There were two modes of operation: the window was highly specified and the paving was merely suggested with certain points to attend to through the design.

(5) Private House in Wandsworth

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

“The sense of being in lean times and those potentially being very productive is something that I want to pause on now, given the time that we are in at the moment; to reiterate that it can be something that’s productive.”

Were you happy with the final outcome of such an improvised project?

Very happy indeed, because it was a complete collaboration. It was entered through abandoning your own sense of authorship and opening the project up to chance and to open-ended processes. It highlighted that the role of the architect is more about bringing people into conversations and trusting them to find their own way, to find ways of articulating different strands, rather than this insistent notion of the architect as author. At the time, having just set up my own practice, I found this incredibly interesting and instructive.

It’s interesting to think about this time. I had just lost my job in 1990 during very lean times. I opened my own practice, not as some great planned event, but really because I had nothing else to do. The sense of being in lean times and those potentially being very productive is something that I want to pause on now, given the time that we are in at the moment; to reiterate that it can be something that’s productive. I was fortunate in the people that I met, but to some extent we were making up these projects as we went along.

(6) Historic photo from the airbase

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

Gina also had a little house in Northamptonshire, for which she asked us to design a patio. (6) When I went up, I discovered that this house was on an old American airbase that had been used to drop the Resistance into France, Norway, and the Netherlands during the Second World War. I thought this was fantastic and started to read around the history of the base. I decided to encourage Gina to spend her budget on designing a photographic apparatus around one of the old bomb ponds, rather than a patio. I made reference to a set of Anselm Kiefer paintings, which for me were highly suggestive of the scorched earth of Germany after the war. Heavy lead wings were fixed to the painted images that could be angels or crashed aircraft over the burnt stubble fields. They seemed to relate directly to the strange site in Northamptonshire. We began to think about this lead-like wing, hovering over the stubble of the arable land on our site. We thought this might hark back to the lost memory of its recent past. It’s an amazing site, it was an airbase for secret operations during the Second World War, then a nuclear missile base and then it was a car scrapyard, before being used as Set-aside under the European Union agricultural incentives in the 1980s. It was a bit of nowhere that had this strange history - it was really interesting to try and bring up some of these stories. These photographs are made from a mix of physical collage and slide projections on to the collage. We were trying to make this representation of a building by the water for Gina to photograph but that would also be like a lead wing, camouflaged in the arable fields. We were trying to get a feel for the form of the thing and in a sense to convice Gina of the idea that we might make something like this. After all, we were meant to just be designing a patio.

(7) Site photo

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

(7) Here’s a photo of a much younger version of me with Simon Storey, the builder. He had been a ballet dancer at the Royal Ballet, but felt it was too self-regarding and that building was a more appropriate activity for being in the world. He built a lot of my early works and was completely vocational in his outlook. In this image he’s describing the whole architectural concept of the building to two concrete foundation workers - he felt that everybody needed to know what the building was about.

(8) Early stage drawings of The Shack

[Images courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

“I mean that about Wright; his inconsistency was probably the most fertile and influential thing in the twentieth century. He’s interacting with Le Corbusier, who is copying him, and then he’s copying Le Corbusier. Mies is copying him, then he’s copying Mies. People like Kahn, Utzon and Stirling could never have been who they were if it wasn’t for Wright.”

[Images courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

“I mean that about Wright; his inconsistency was probably the most fertile and influential thing in the twentieth century. He’s interacting with Le Corbusier, who is copying him, and then he’s copying Le Corbusier. Mies is copying him, then he’s copying Mies. People like Kahn, Utzon and Stirling could never have been who they were if it wasn’t for Wright.”

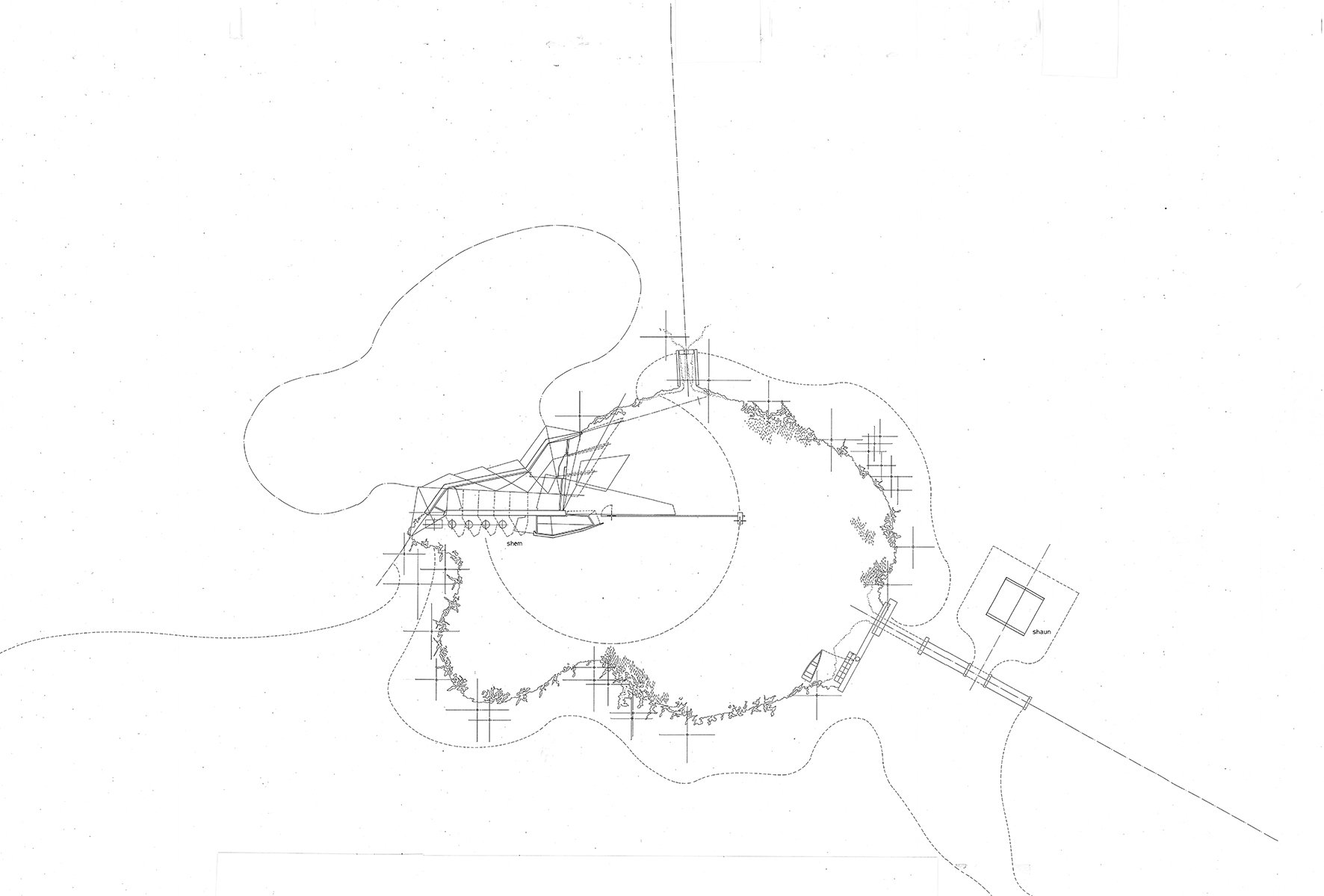

(8)There were no working drawings at all. We built a model, put it on the site and Simon built it from that. On the opposite side of the lake, Gina had this strange hut that was given to her by her father. I love in Finnegan’s Wake that you have these two characters, the brothers, Shem and Shaun. Shem is strange, complicated, dirty, creative, fertile and part of the earth, whilst Shaun is ordered, cold and austere. These two archetypes were linked to our two little structures, the shack and the hut. We called them Shem and Shaun; that pairing became part of the project.

This work differs quite considerably to the kind of architecture that you’ve produced in more recent years. In your Drawing Matters publication you spoke about how you don’t really return to your sketchbooks and that that process was the first time you had looked at those sketchbooks in 25 years. Is that similar for references and books? Are you still reading references from this era today?

There is this requirement of the modern age to be superficially consistent and I really don’t understand it. I don’t know why you would be consistent throughout your life, it doesn’t seem to be a particularly interesting state. It could be that I’m not consistent over time and that I used to do things like that and now I do something else, but it might be that I would do something like that next year again if I get the opportunity. I’ve been reading a lot about Frank Lloyd Wright recently and the sheer variety of his output. Ralph Waldo Emerson said that, “foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds adored by little statesmen and philosophers and Divine’s, but with consistency, a great soul, has simply nothing to do.” I mean that about Wright; his inconsistency was probably the most fertile and influential thing in the twentieth century. He’s interacting with Le Corbusier, who is copying him, and then he’s copying Le Corbusier. Mies is copying him, then he’s copying Mies. People like Kahn, Utzon and Stirling could never have been who they were if it wasn’t for Wright. The sheer breadth of his reach, which is a function of his inconsistent mind, seems to be a great example; I think consistency is highly overrated.

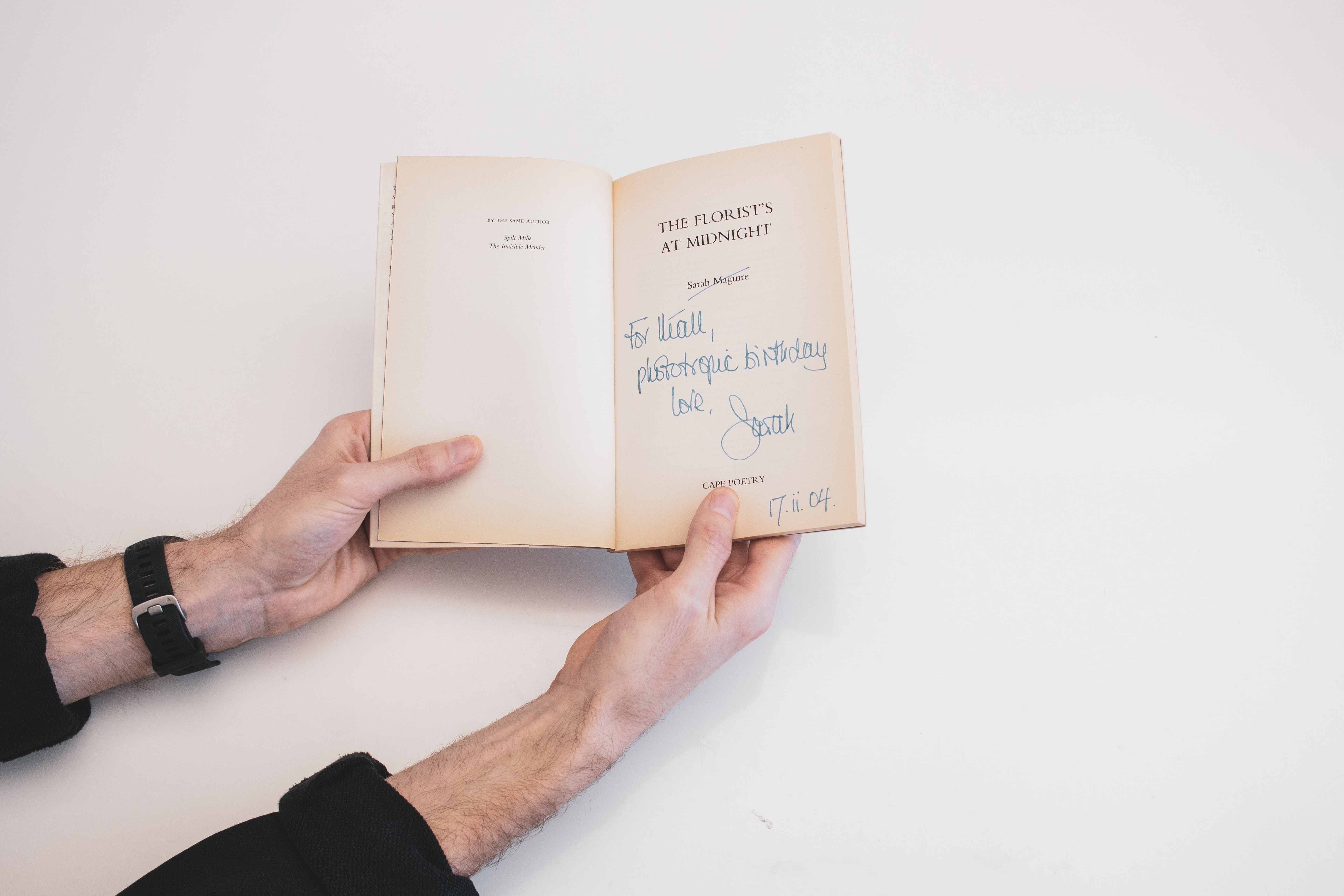

(9) ‘The Florist’s at Midnight’ / Sarah Maguire

(Jonathan Cape Ltd (8 Nov. 2001)

“Back in 1996 and on the border of the digital era, it seemed to be a really interesting subject; the idea of the landscape that mediated between the market and the natural rhythm of the seasons through telecommunications.”

(Jonathan Cape Ltd (8 Nov. 2001)

“Back in 1996 and on the border of the digital era, it seemed to be a really interesting subject; the idea of the landscape that mediated between the market and the natural rhythm of the seasons through telecommunications.”

The last project we did on that site in Northamptonshire, Phototropic, was based on poems written by a friend of mine. We decided to put a radio installation on the site that would broadcast a fixed radio signal, helping to bring elderly American airmen back to the runway when they returned to visit their old airbase. The concrete runways have now been dug up so are completely invisible at ground level. So, the radio signal we created can be picked up at Heathrow, letting them navigate their way home to find their site. (10) At the time, my friend Sarah Maguire was writing these beautiful poems about industrial flower farming. I loved the idea that this site, which had always been something else - Set-aside, or scrap yard, or nuclear missile base - seemed like the whole history of the modern British landscape had run through it. So, I liked the idea of installing industrialised polytunnel flower farming here. Sarah had made these beautiful and ethereal poems about the unnatural nature of flower farming.

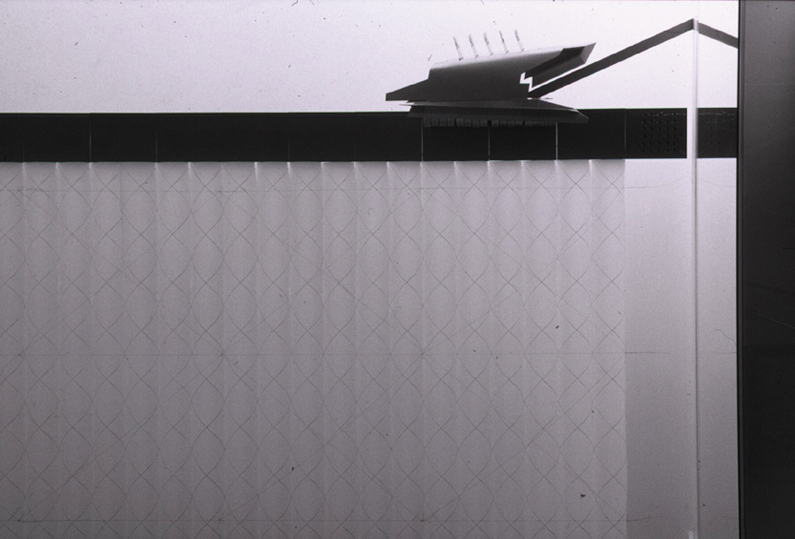

(10) Physical model of The Shack

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

YEAR-ROUND CHRYSANTHEMUMS

In mid-July

they think it is winter

All it takes

is an hour’s incandescence

at midnight

and their day

germinates: twenty-four hours

makes two

Year-round chrysanthemums

the long nights

make you rich

and fecund

Your bunched, curled faces

magenta and saffron

phototropic with desire

inexorably riding the light

(11) Phototropic

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

...which has sadly never come to fruition?

I don’t think it was ever intended to do so. It was such a fertile landscape that I could have done any number of projects on it. We got one built and that was enough probably. Gina took some photos recently of the little photographer’s hide. It’s more than 20 years old now and it’s quietly mouldering away.

All photography by Tim Lucas unless otherwise stated.

Website