8. i) Níall McLaughlin

Architect

London - UK

‘Losing Myself’

This is a transcript of a discussion held between Níall McLaughlin and Arch-ive, as part of the Architecture Foundation’s ‘100 Day Studio’. Part i discusses The Alzheimer’s Respite Centre in Dublin alongside Níall’s project ‘Losing Myself’. The full interview is available to watch here.

As a brief introduction, Níall and I had a couple of preparatory sessions, whereby we concluded that the talk would fall somewhere between an interview and a lecture. As such, a presentation was compiled in Powerpoint, allowing the interview to transition between scales, highlighting the wide-ranging scope of sources. The interview itself felt like the development of a lecture, allowing Níall to discuss specific and critical references, whilst talking freely about projects and processes.

I think it is important to note your slight reluctance on addressing the literature that impacts your architecture. You were apprehensive about the insinuation that book equals building; that it could easily be misunderstood as you read a certain piece of literature and a building magically appears. During one of our discussions, you spoke about loam as an analogy for your relationship to reading and literature.

(1) Loam diagram.

[Image courtesy of https://www.thoughtco.com/soil-classification-diagram-1441203]

“The layers of soil that build up in a garden or woodland. Whatever grows out of that loam is naturally dependent on it, but the relationship between the nourishing substructure growth is not as direct, or as necessary, as some people think.”

I do have a scepticism about architects showing off all their books and laying claim to a deep intellectual life that somehow has an equivalence in their buildings. I think I am sceptical to a degree about the idea that there’s a whole set of texts that I have read and a building that I have built and there is an equal sign between the two of them. It’s perfectly clear that many architects are extensive and careful readers and that reading must have some impact on the buildings that they are creating. However, unpicking the nature of that relationship seems to me to be trickier than creating any direct equivalences. I worry when I find myself, or others, at lectures reading from a text, and then the next thing is there’s a photograph of the building, a direct equivalence between the two appears. (1) So, this is the idea of loam; the layers of soil that build up in a garden or a woodland. Whatever grows out of that loam is naturally dependent on it, but the relationship between the nourishing substructure growth is not as direct, or as necessary, as some people think. That was the metaphor I was using when discussing the tension in this lecture.

(2) ‘The Artless Word’ / Fritz Neumeyer (MIT Press; New edition, 1994)

You have made reference to ‘The Artless Word’ by Fritz Neumeyer about Mies van der Rohe and the way books were loosely connected back to his notepads and sketchbooks. It didn’t point to a set reading and its direct influence on one building, instead it was broader than that, a connectedness.

The book was written by Fritz Neumeyer who went to Mies van der Rohe’s archive at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (2) Mies was meticulous and Neumeyer quickly realised that he had written scrupulous notes in the margins as well as retaining receipts for all the books he had bought. It’s a really beautiful text, re-constructing the intellectual and imaginative development of Mies van der Rohe through his reading in parallel with speeches, lectures, and the buildings that Mies was constructing at the time. At the beginning you see many rich and complex threads within his reading; the biology of the cell, German experimental theatre, neoplasticism...all of these readings are coming together bit by bit, assembling a consistent interior world of influence. As he grows older, you see a more and more laconic expression of his view of the world. For an architect of my appetite, it was a book that I really enjoyed.

During your work on the Alzheimer’s Respite Centre in Dublin, you undertook a lot of research into neurology and the brain. Were you reading this material prior to your engagement with the project? Is it an area of research that you continue to reflect upon?

The brief for the Alzheimer’s Centre was remarkably interesting. The Alzheimer’s Society of Ireland said ‘we don’t know anything about architecture, and you don’t know anything about dementia, so we’ll spend some time educating each other’. A fantastic invitation from a client. They asked us to read around the subject of environmental design and the way in which it can impact people with dementia, whilst also requesting we immerse ourselves in the lives of the people using their daycare centre. The building took a decade to design and build, but for me, it began a very long engagement with trying to understand the relationship between the underlying human cognitive functions and the way we experience space. Space is a word we take for granted, particularly as architects. It is a word that architects have used since Kant as a badge of their identity. But we rarely stop and think what we mean by it; what its implications are... For Kant there’s a balance between space as an innate capacity of the mind and something that we learn to comprehend through our development? I’m lucky enough to teach at UCL where there is fantastic research in neuroscience looking specifically at navigation and spatial thinking. It is trying to understand the neurological underpinning of our idea of space. My initial research began with the Alzheimer’s Centre but it has developed into 20 years of extensive reading around the subject.

(3) A drawing from one of Níall McLaughlin’s notebooks investigating the geography of the brain.

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin]

“The Alzheimer’s Society of Ireland said ‘we don’t know anything about architecture, and you don’t know anything about dementia, so we’ll spend some time educating each other’. A fantastic invitation from a client.”

Throughout the project, you often placed yourself in the space, developing your own relationship with these ‘wandering plans’. You put yourself in the mind of somebody with dementia, considering their daily path and how they may navigate space.

As a practising architect coming to a new project, you read around the subject, meet new clients and try to understand the way in which they are thinking. Particularly for people with dementia, that’s quite a difficult thing to do. You are trying to experience the world through a condition that you can’t really imagine. I spent a lot of time trying to think about the predicament of someone living with dementia and imagining the way in which a building might serve to place people back in the world. Dementia undermines the basic function of navigation and memory, altering your perception of how you are located in time and space, elements that are fundamentally linked at the most basic level of your consciousness. With dementia, the hippocampus often directly suffers. This is where space and time are processed and made into representations of the world. It becomes difficult to plan what will happen next when the stability of both time and place in the present is reduced. You’re in this state of endless, often quite anxious wandering. As a result, I began to draw plans of people wandering around a building, where there would always be views to a variety of gardens, and ensuing differences in light, smell...I found a number of correlating plans, one of which was Mies’ ‘Brick Country House’ (4). It was an almost paradoxical task, to take Mies’ building which is all about extending to the furthest horizon and to drop it into an eighteenth century walled garden. I also looked at Barragan’s house in Mexico City and Schindler’s King’s Road House. It was an interesting task to find the commonalities between the plans. I found myself flipping between reading and experience and then back to the plan again.

(4) ‘The Artless Word’ / Fritz Meumeyer (MIT Press; New edition, 1994)

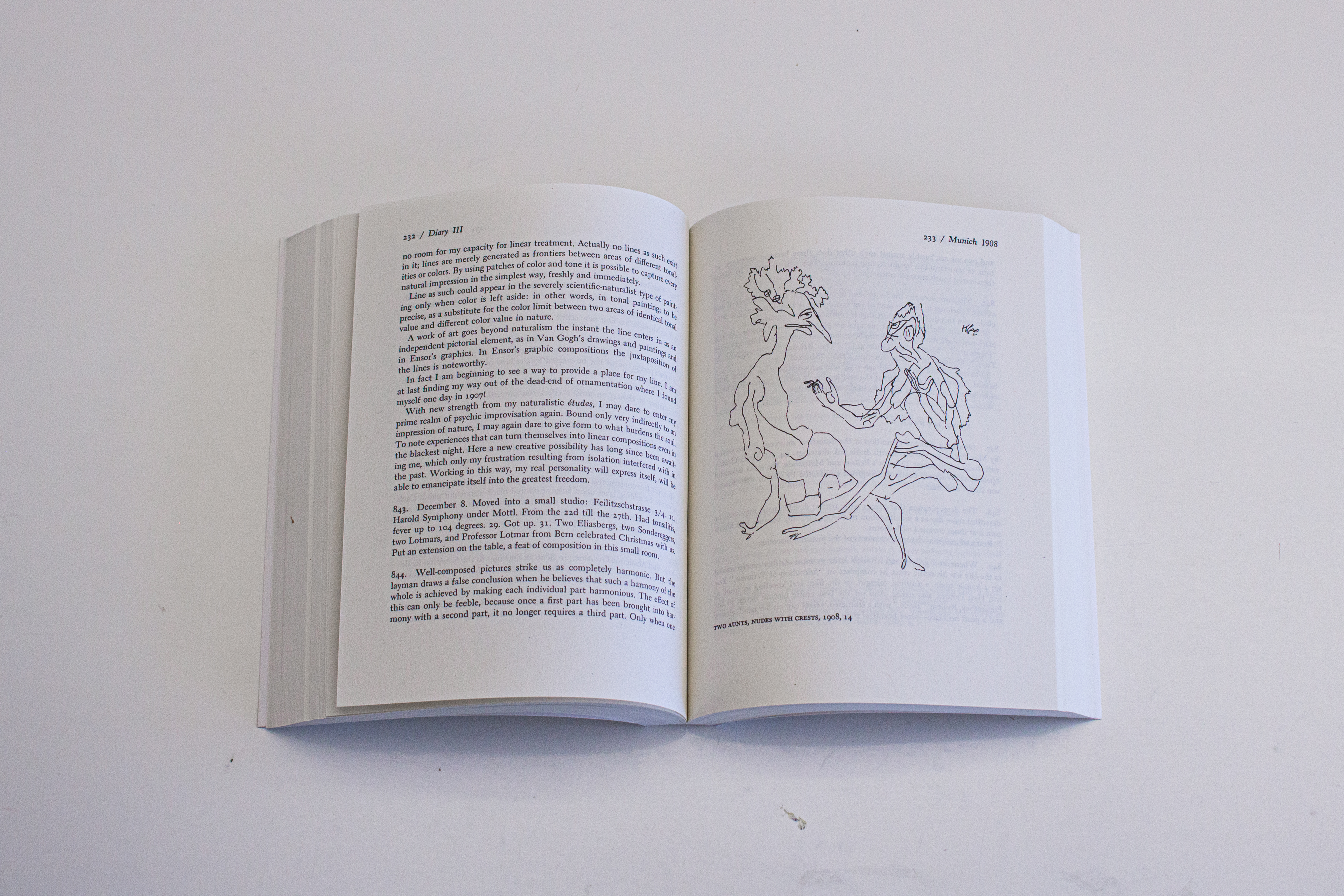

There’s a very ordinary book called ‘Dementia Reconsidered’. It’s a practical book on what it’s like to live with dementia, written in the 90s by Tom Kitwood. It was originally for social workers and carers, but it revolutionised the way people thought about dementia and person-centred caring. When I read this book, I began to think about Paul Klee’s drawings. (5) I’ve noticed that Klee’s drawings are always dealing with the predicament of the individual in space; from the moment of your birth, through your development, to ageing and the decline of your ability to navigate and understand your place in the world. Klee seems to have drawn the autobiography of an individual. I began by looking at writings by and about Klee, to try and find an avenue into the project. In truth, his drawings are his most eloquent expression, but it did lead me towards an area of thinking related to empathy and space and a group of German philosophers in the late nineteenth century who I’m sure would have been known by Klee. They were investigating the relationship between the body and space, how we understand where we are in space. Klee made a sequence of drawings that investigated this predicament. There’s a lovely collection by Harry Francis Mallgrave, with essays by various philosophers and their thinking. The degree to which the mind understands volume and space, allows us to measure the scale of our own body: a known thing, against other things which we move out into. That was a fascination that led me towards people like Thomas Metzinger. An amazing contemporary philosopher who investigates the idea of the individual and how their mind creates what he calls ‘fully transparent representations’. For example, the idea that you are you, talking to me on a Zoom call, is what he would call a ‘fully transparent representation’. It’s constructed within the mind as a coherent representation of the world, but the sense of it being a representation is something that we have lost. So, we imagine that there’s a relationship between an I, who’s in here, and then an ‘out there’, which has lots of objects and other people in it. He’s saying that that’s a fiction and a hallucination. He does these wonderful experiments to show why that is so. He’s continuing to develop that German line of thinking, from Kant to Schmarsow and Vischer, right into new thoughts about neuroscience in the twenty-first century.

(5) ‘The Diaries of Paul Klee, 1898-1918’ / Paul Klee (University of California Press; Illustrated edition,1992)

“Klee’s drawings are always dealing with the predicament of the individual in space; from the moment of your birth, through your development, to ageing and the decline of your ability to navigate and understand your place in the world. Klee seems to have drawn the autobiography of an individual.”

“Klee’s drawings are always dealing with the predicament of the individual in space; from the moment of your birth, through your development, to ageing and the decline of your ability to navigate and understand your place in the world. Klee seems to have drawn the autobiography of an individual.”

This topic obviously meant a lot to you, both personally and as a practice with ‘Losing Myself’ at the Venice Biennale in 2016. Do you still continue to research this topic and incorporate it within your architectural practice?

The project at Venice became well known, but was actually part of a longer project I called ‘Losing Myself’. We started a research group in the office to begin to formulate that thinking once again. We made a website that hosts a series of podcasts and conversations with people about dementia. We look at the illness from all sorts of angles. (6) Sebastian Crutch, a neuropsychologist and expert on certain kinds of dementia, talks in great detail about the underlying neurological processes. On the other hand, we spoke with a wonderfully articulate woman called Helen Rochford Brennan from Ireland who highlights her experience of living with the illness. She is able to talk in absolutely lucid detail about the experience of having dementia, describing in painstaking detail how she navigates through the city, through her house and the way in which she uses cues. It’s really fascinating, because, for her, the labour of navigation, the labour of being in space and orientating herself in the world is such a conscious act of intelligence that it makes you think about your own relationship to space. The way you move all the time, without even thinking or knowing about it, is something that she has to constantly work to achieve. It brings you to a level of consciousness that the thing she is losing, that she’s applying all of her intelligence to holding on to, is the thing that we have that we are not even aware of; but seems so central to the subject of architecture. In a sense, that is a major development from the research as we talk to anthropologists, philosophers, neuroscientists, psychologists, and care workers. Not just about dementia, but expanding our conversations about space and navigation more generally.

(6) Interviews conducted as part of ‘Losing Myself’.

[Image courtesy of http://www.losingmyself.ie/about/]

[Image courtesy of http://www.losingmyself.ie/about/]

It’s amazing that this research has carried on and become such an intrinsic part of your practice. Like you said, we don’t really consider our relationship to space, it’s never a conscious act to consider your position. It almost feels that our current situation, working from home and everything being done over Zoom, has made people more aware of their surroundings, more conscious of the space in which they are currently spending all their time.

Something I found with this project, which I think is fascinating about an architectural life, is that architecture is a synthetic task. You’re always bringing together lots of different disciplines and you generally know a bit about everything and not a lot about much. A lot of the skill is about integrating and cross-referencing different conversations and bringing people with real expertise, whether they’re joiners, engineers and so on into the conversation. This allows all these various elements of expertise to intertwine through your own mediation. When we went to speak to these very high-functioning thinkers about the subject of space and dementia, asking all the dumb questions, we uncovered just how siloed some of their thinking is. Neuroscientists at UCL kept talking about the hippocampus’ ability to create maps, which they were showcasing through these rather beautiful experiments, whilst Tim Ingold, the anthropologist, was absolutely resistant to the idea that the brain makes any maps at all. These two separate groups had developed significant reputations in their fields but had never been brought into contact with one another’s thinking before. I think that is something that architects can do, because the slightly promiscuous side of our reading and thinking does have a virtue when it comes to developing a much broader experience; that you can then bring these disciplines together in new ways.

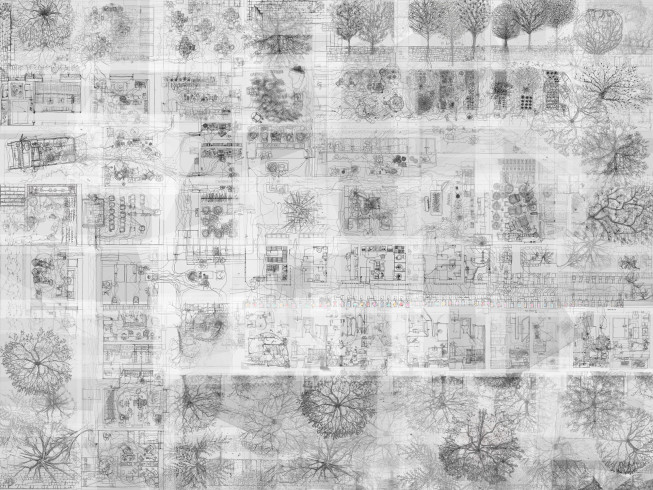

(7) ‘Losing Myself’ drawing.

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin Architects]

“The phrase ‘losing myself’ comes from Rebecca Solnit, quoting or referencing Walter Benjamin, where she says ‘to be lost is to be truly present’. I love this idea, that in those moments in our lives where we feel a little lost, we’re far more present in the world.”

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin Architects]

“The phrase ‘losing myself’ comes from Rebecca Solnit, quoting or referencing Walter Benjamin, where she says ‘to be lost is to be truly present’. I love this idea, that in those moments in our lives where we feel a little lost, we’re far more present in the world.”

Definitely. It’s a fantastic resource that has been made available online that looks at connecting these multiple kinds of expertise in a single platform. I have here your short video from Venice, which has been placed alongside you and colleagues undertaking the drawing for the project.

This project was a collaboration between myself and my teaching partner, Yeoryia Manolopoulou. It was a joint project and we engaged ex-students to help us draw. We brought them to the studio and tried to make these drawings whilst thinking about individuals with dementia in the Alzheimer’s respite centre; to make a plan that was witnessing their experience of the building. Architectural plans have an allocentric quality, you can see all of the building, all at once. That’s the exact opposite to what someone with dementia is experiencing where they can only witness fragments, which are continually falling away. (7) We tried to use the act of drawing to reconstruct that fragmentary experience. The project was a way to interrogate the convention of the architectural plan and investigate the way in which we conceive buildings and to ask whether people who have dementia have any way of understanding that conception. The phrase ‘losing myself’ comes from Rebecca Solnit, quoting or referencing Walter Benjamin, where she says ‘to be lost is to be truly present’. I love this idea, that in those moments in our lives where we feel a little lost, we’re far more present in the world. I was thinking about this idea of presence in relation to architecture and how so much of our time we spend on a kind of automatic pilot and it’s only when we have questions, or we’re lost, or our world is disrupted, that an active sense of presence comes forward. The phrase ‘losing myself ‘contains an idea of the architect’s own intersubjectivity: that you’re constantly trying to put yourself in the situation of somebody who is not you, that you have to somehow be lost on their behalf. It ended up with this projection on the floor, which is constantly drawing and erasing itself through a cycle of 24 hours.

(8) ‘Losing Myself’ project at the Venice Biennale, 2016.

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin Architects]

[Image courtesy of Níall McLaughlin Architects]

All photography by Tim Lucas unless otherwise stated.

Website