6. Alisha Morenike Fisher

Environmental Facilitator, Educator and Founder

Bristol - UK

‘Building Social Change’

A trip to Bristol saw Arch-ive welcomed into the home of Alisha Morenike Fisher, an environmental facilitator, educator and founder. Alisha founded Black Females in Architecture in 2018. She also works as a Director alongside her Co-Directors Selasi Setufe, Neba Sere and Akua Danso, a network and enterprise that aims to increase the visibility of black females and black mixed heritage females within the built environment. They are specifically looking to tackle inequity and a lack of representation across the industry and now have over 350 members globally. Sign up to their newsletter here to receive the latest news and become part of a valued and critical network.

After finishing her Part 1 architectural degree, Alisha co-founded 3.09. This later transformed in to Migrant’s Bureau, a multi-disciplinary practice investigating social design and urbanism surrounding disenfranchised and migrant communities. Through an understanding of people’s culture, geography and social circumstance, Migrant’s Bureau curate, research, design and facilitate environmental and sustainable interventions that respond to these needs. They have recently released an excellent podcast series, which can be found here.

The ensuing interview offers a fantastic insight into Alisha’s journey to date and her relationship with politics, space, inclusivity and the built environment, all centered around a discussion on the literature that has influenced her work and life.

You are approaching this interview slightly differently to some of our previous guests, having not completed formal architectural training. As a brief introduction to the interview, would you mind telling us a little bit more about yourself?

I got into architecture through trying to understand more about the politics of space. A few people suggested I look at interior architecture, but it wasn’t for me; I didn’t just want to do the inside, I wanted to be part of the whole thing. All the different processes and how they work. I built a real curiosity about how different people navigate in different spaces. In that sense, I guess my interest is more orientated towards sociology and anthropology. It’s all about people’s different experiences, how there’s not a ‘one type fits all’ solution. We all have to make sure that we are being a bit more inclusive (I don’t really like that word), but more inclusive in the way we approach things.

And you’re currently working for Migrants Bureau? But you were also involved in setting up another practice before?

Yes, 3.09. It was a collective. I ended up sitting next to my co-founder at an event, chatting away. He suggested we do a competition and I said “cool, but I don’t really know you from anywhere [laughs]”. But it really worked out. We linked up with other people digitally and took it from there. I was in Hull, he was in Manchester, another in Oxford and another in Mexico. It was a bit all over the place, but we managed to make it work. After the competition, we began to think about how we could get more people involved. It was at this point we moved away from a collective; we wanted to create more accountability. For us, we felt that the collective lacked ownership, that people were unwilling to take ownership of the work they were producing. As soon as we provided people with that responsibility, to lead that project, to follow a budget, the practice really evolved.

And 3.09 was created straight out of university?

It was! I was really frustrated at the time. Architecture school just wasn’t exploring all the options available and I found that suppressive. I understood the process of criticism but it felt like there was a wider, more destructive nature to the course, a real lack of people actually listening and understanding. It felt like everyone was constantly on ‘attack mode’. Not just directed at me, but other students, other tutors, other critics. It felt very one-dimensional - ‘I’m the teacher, you’re the student, this is how you should learn…’

It’s amazing that you had the confidence and the ability to finish university and start a company. It would have been a lot easier to quit the profession but you did the complete opposite!

Well, not quite. I kind of did quit the profession. I’m in architecture, but I’m not in architecture. I’ve never actually had a Part 1 job. I became really interested in environmental studies, which led me to landscape architecture. I found that too horticultural, not enough about the climate, climate justice, indigenous spaces. There was very little exchange around these ideas.

Completely. I suppose architecture school can be very inward facing, in all senses. From the projects you are undertaking, the institution itself, the relationship with the city and the campus. It’s interesting that you’re always looking at the bigger picture. Would you say a lot of your literature has been influenced by your time at university?

Quite a lot is from university. However, one of the major issues I had with university was the lack of information on my culture in architecture. Nigerian culture is very specific, but trying to understand more about African architecture? It was something that was never really discussed. At the time I asked my tutors if I could take a term off. I couldn’t write my dissertation as there was no literature available on African architecture in the library. The frustrating thing was, it wasn’t for the lack of publishing, just the lack of availability in the university library. I couldn’t afford to buy all those books but to get my dissertation done, I had to find a way around that.

I ended up crowdfunding for a trip to 6 African countries in 6 weeks. With no available literature, I decided I needed to take a term off, to go and see what was really going on there. Sadly I didn’t manage to travel to all 6 cities, instead I ended up in 3 for 4 months altogether. For the first month I was in Nigeria learning about a very specific type of urbanisation to that place. I then went to South Africa, during the Fees Must Fall protest. There was an amazing energy around the students. To be honest, I was merely an observer, but I tentatively watched and listened as they rose up. Alongside this research, I began collecting books about understanding the city; the residents, the common spaces, the nuances of the politics of different spaces.

“It questions the social context of architecture and the implications on the built environment. It’s largely US based, with some fantastic maps looking at race and class and their relationship to land, planning, policy-making, education. It really connected a lot of my thoughts together.”

One of the first books I began to look at that connected a lot of these themes was Andres Lepik’s ‘Afritecture – Building Social Change’. Another recent book is ‘…and other such stories’ by Yesomi Umolu, published in conjunction with the Chicago Architecture Biennial. It really questions the social context of architecture and the implications on the built environment. It’s largely US based, with some fantastic maps looking at race and class and their relationship to land, planning, policy-making, education. It really connected a lot of my thoughts together. It was recommended to me at a book show at The Building Centre, hosted by Eyesore. A lot of African cities are not as structured as UK or US cities. In Lagos, where my family and I are from, it’s chaos and eclectic. The characters of the city are a mix of chaos at different levels which can be thrilling and horrifying at the same time. A weird balance of feelings that pulls you in.

Where do you store them, and how are they organised?

Mainly in the living room. There’s a section on architecture and the city, with a particular focus on understanding it from an African context. Then there’s a fiction section and another on books relating to spirituality. It’s a real mixture of different things.

Since my dissertation I have started investing in more books on African architecture from different tribes. I find I don’t extract much from literature on African architecture by non-diasporan Africans, I try to make an effort though.

Did you find that you spent a long time reading books that you really weren’t getting anything from?

Yes, for sure. Especially at architecture school with that initial reading list. I think it only hit home when my tutor was specifically talking about urbanism. That really connected a lot of my thinking. When I was presented with Le Corbusier I was really intrigued, really interested. But I was disappointed about the lack of transparency. No one was discussing the appalling issue he had with people not being able to stay in his house for very long. No one was talking about his failures. I feel that if we can’t talk about his failures, how can we get to a point where we can really learn from these people, truly understand them in their entirety? We have to learn from their mistakes.

“Everyone is boxed in and that’s not healthy. What happens if someone is in that grey area? What happens if someone is slipping between the cracks? It shows how important it is to look out for one another, but also the importance of understanding that we’re all learning from one another.”

Is there one book that you would point to as being the most influential throughout your time practising?

Probably the ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ by Paulo Freire. It was one of the first books I read where the focus wasn’t necessarily on architecture, but more about the underlying system. It taught me the importance of understanding how we work and the real lack of any communal aspect. It was really intuitive in its description of oppression. We live with a system that can oppress us in so many different ways; in reality we’re all kind of oppressed. You don’t necessarily see it, until it directly effects you but it impacts us all. Freire investigates how if we are all oppressed, then how do we communicate those oppressions to one another? In what spaces can we talk about them? Now, in our culture, it’s related more closely to categories. If you have mental health issues, you have mental health therapy. If you have these issues, do this…Everyone is boxed in and that’s not healthy. What happens if someone is in that grey area? What happens if someone is slipping between the cracks? It shows how important it is to look out for one another, but also the importance of understanding that we’re all learning from one another. I do believe in social equity, but I feel to get there, we need to be able to listen to one another. To see what effects different people and how.

Has that book fed into your role with BFA and trying to create those kind of spaces where that discussion can take place?

Yes, definitely. Recently we had a big discussion about our role as gatekeepers. As black women, we hold the keys for other black women who’s experiences are not like ours. How do we communicate that? How do we highlight these women that are completely different to us? Some of them are parents, some are students, some are in different places, some speak 5 languages, whereas some just want to do architecture, or environmental architecture…We were looking at how we can try to make sure we are creating opportunities for people to be seen.

This has also brought up a lot of dialogue on transparency. One thing i’ve realised, is that if we’re not transparent about where we’re at currently, then people don’t feel like they can raise an issue. Through transparency, people develop commonalities. This leads to dialogue, and ultimately, a more open society.

I think that’s something that’s come out of the Black Lives Matter movement, that it is very easy to judge somebody about what they say and condemn them. There’s a contentious area where if you condemn someone they then won’t speak about it and internalise those thoughts, which can be dangerous. I think transparency is key, the ability to learn and be held accountable, but also to have the option to learn, which sadly some people don’t have. How do you open up avenues for everybody to learn about those issues? Which is one of the amazing things about BFA - that you are trying to create those networks of dialogue and education. Is literature something that is readily spoken about at BFA?

Yes. The events team co-host BFA’s book club. We’re currently trying to do it quarterly until we can get a system in place for this new era of digital living. We’ve had 2 so far. The first discussion was specifically looking at race and the following on Bernardine Evaristo’s ‘Girl, Woman, Other’. It’s a fascinating book that portrays the experience of 12 women, all at different stages of their lives. It outlines all these incredibly different characters who have had incredibly different experiences, but you soon realise how intertwined they all are. It’s an amazing exploration of these 12 people navigating their way through life and a vital message for how individuals relate. There’s a nuance there, explaining how as human beings we can mess up, but we can also undo. We’re not perfect, but we can strive towards something better.

“We talk about how specific books can be hard to grapple with, depending on the content. One of them expressed how they kept jumping from one thing to another and for them, the entire book was really hazy. I’d never thought about that before, how your life experiences completely alters the way in which we can consume literature.”

How do you work with books? Do you take notes, annotate, read aloud, draw…?

It really depends on the book. In some books I’ll annotate, in others I’ll have book marks, sticky tape…interesting bits that I want to remind myself of later. During COVID, I’ve tried reading multiple books at the same time, full well knowing it won’t work. So I’m trying to use bookmarks to allow myself to think, to just generally be curious and question things even more.

Are you writing much at all? Is there any reading that is feeding into your work within, but not within the architectural profession as you previously described?

I journal quite a bit; a notepad by my bed. It depends on the occasion. I think my reading is fitting into my work at Migrant’s Bureau. Less so at BFA, where we act as facilitators, making sure systems are in place, asking the right questions, hosting the events that suit members…It then becomes an opportunity for our community to use these facilities. But, with Migrant’s Bureau, I feel like there’s a lot more space to be individual, to share my interests. We’ve recently started a monthly book and media club, which is kind of similar to this. It felt like a bubble has been burst, there’s so much to learn. There’s a concept called bubble-hopping, where you go outside of yourself, outside of your own experiences to try and learn what other people might be going through. In this list, there’s literature on mobility and sensory challenges, ageism, so many different categories. You really learn how different people are affected and the politics around that. At the moment, we’re all using it, but we’re not all benefitting from it. How do we create more dialogue? In our team, we have people with dyslexia, PTSD and other challenges. We talk about how specific books can be hard to grapple with, depending on the content. One of them expressed how they kept jumping from one thing to another and for them, the entire book was really hazy. I’d never thought about that before, how your life experiences completely alters the way in which we can consume literature.

Would you like to be increasingly involved in earlier education? Is that something that BFA are looking at? Or Migrant’s Bureau? With more focus on curriculum.

As Migrant’s Bureau, we’ve done a few workshops in the past, to try and get young people involved. The problem we’ve found is that it’s such a lengthy process. You can’t just teach kids and that’s it; you have to also make sure that they have the opportunities, to have some work experience, to be immersed in the profession. There’s then a whole politics around that, are they doing it voluntarily? Are they getting paid fully, or just expenses? That’s when everything can start to unravel, because people don’t have the infrastructure. It’s critical that work experience is paid at a younger level, to open up the field to all.

It also relates to understanding. As BFA, we try to be more honest about our industry. We cannot perpetuate the lifestyle. We have to tell the truth. It is a long course, it’s going to take you 7 years, although that 7 years could actually end up being 10 years. I never got told that and now I’m not really sure if I want to stay in architecture. If I do stay in architecture, it has to be in a different way. I need to work it out. I think it’s perfectly okay to go into architecture if you know all the parts to it, at least the majority of things. If you don’t, then it can become a really big problem.

If you could re-discover one book, what would it be?

I want to read the Bible, the real Bible. The Bible as we know it has multiple books missing, which really intrigues me. Anything that’s missing, I want to read. I found out that the original book is in Ethiopia and has 81 books. How is that even possible? It’s been renamed and split into stages, multiple books. I find the Bible quite oppressive so the more my friend spoke to me about this original Bible, the more I became fascinated with it. There’s so much missing from our version of the Bible, it’s been edited so heavily to fit into Western culture. I’d love to read it and see if things have changed, or stayed the same. Why would someone even want to change it? What’s missing there? What’s been left out and why?

Absolutely. It’d be really interesting to see what has been defined as fitting into the western tradition or sphere.

I love things like that. Mystery and drama. I only found out 2 days ago, but the Ethiopian calendar has 13 months. They don’t have a leap year. In their calendar they’re in 2012, but in ours we’re in 2020. I find things like that fascinating.

“Glaeser talks about multiple elements of the city: spaces, disparities, racial tensions, the class system and breaks all these different elements down. I could really see a little bit of myself in this book.”

What book would you recommend every young, aspiring architect to read?

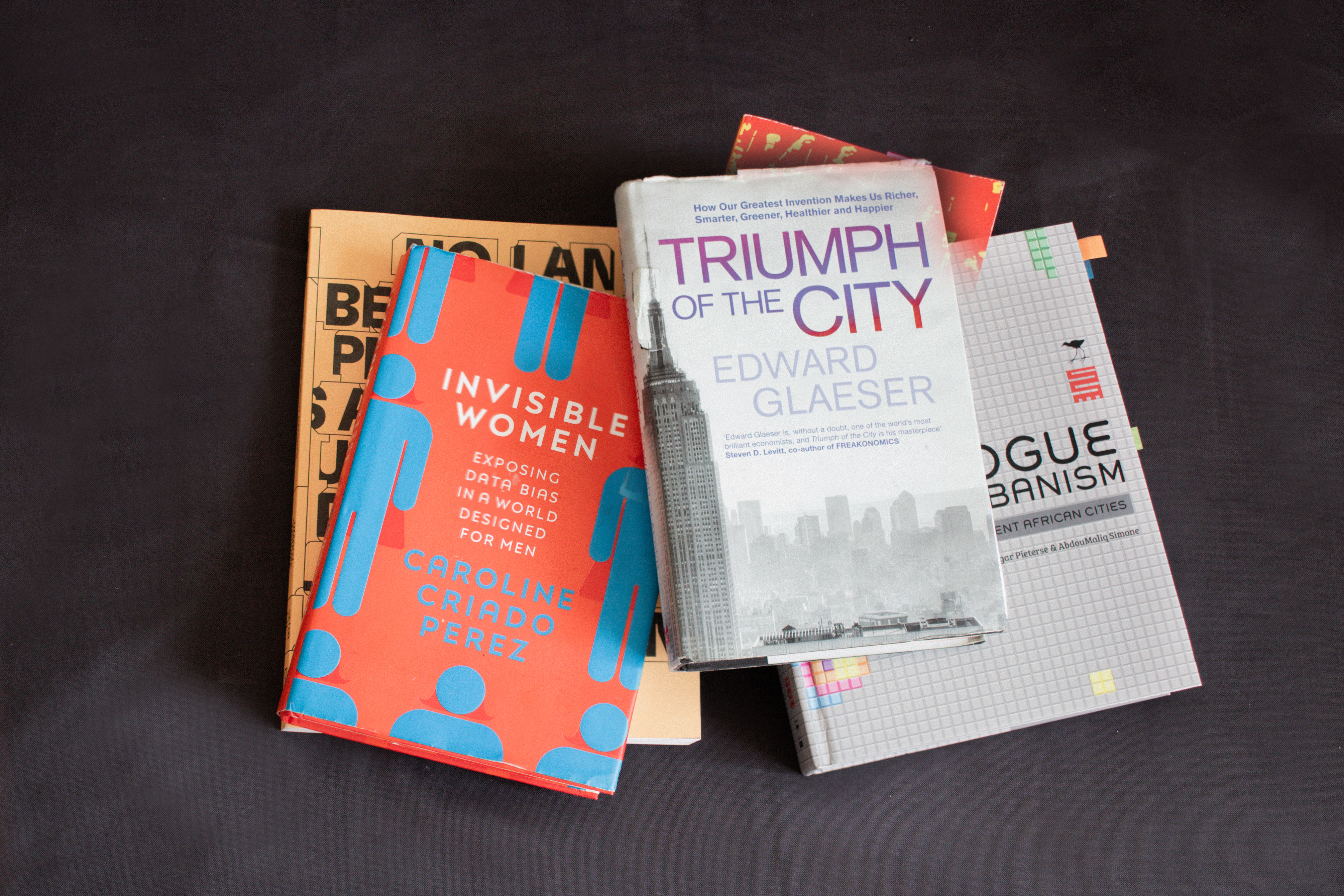

Probably ‘Triumph of the City’ by Edward Glaeser. It was the first book that got me interested in architecture, urbanism, politics of the city…One of my tutors recommended it to me and said you have to read it. I was bored of hearing about Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto. Don’t get me wrong, I love their work, but I just thought to myself, is there anything else?

Glaeser's not actually an architect, but an economist. He talks about multiple elements of the city: spaces, disparities, racial tensions, the class system and breaks all these different elements down. I could really see a little bit of myself in this book.

Another is ‘Estates’ by Lynsey Hanley. It’s incredible. The first time I read it I was completely blown away. It’s about working class environments and how they are affected by different themes, for example, grime, race under a lens of white and black communities or the north-south divide. Having grown up and lived in postwar housing, Hanley traces the history of the estate, ending on a series of recommendations for their improvement.

Also, ‘Invisible Women’. It’s a novel, but it really delves into the spaces around the characters, covering gender bias in our cities. I’d definitely recommend it for Caroline Criado Perez's description of various environments, across a multitude of cities. One of the main topics is on language and how as a society we gender everything. Going back to this grey area, if you don’t fit in to one or the other, you just cease to exist. Even as simple as saying ‘hey guys’ to a bunch of women can be really oppressive. It covers a lot of intriguing topics, for example violence in public toilets. She uses data to help identify the way in which women are disenfranchised in different spaces. At the same time, I read it through a different lens, that this isn’t just about gender, but it could actually be about any of us; how any of us feel in a specific space.

All photography by Tim Lucas