5. Finn Williams

City Architect

London - UK

‘Public Sector and Practice’

We met our next guest, Finn Williams, on a Thursday evening after he had spent the day roaming London, visiting friends and colleagues alike. Firstly meeting up with fellow co-founder of Public Practice, Pooja Agrawal, who would be taking over from Finn as its chief executive the following week. The not-for-profit organisation was created by Williams and Agrawal in September 2017 to traverse the chasm between design and the planning system. Since its creation, Public Practice has placed 177 Associates into local authorities and is forming an exemplary network of built environment practitioners, putting high quality, everyday design at the heart of their practice.

Next, Finn took a trip to the Serpentine Pavilion and met with the designer of the 20th pavilion, Sumayya Vally of Counterspace. Slightly misty-eyed, Finn speaks about his move to Malmö in Sweden where he is taking on the role of City Architect, and the extent to which he is going to miss London and the network he has created here. A city he has lived in since he was 11 years old! With the move looming, Finn leads us through a number of books on Malmö and Sweden that are currently forming the basis of his reading.

The interview is supplemented with the literature that has helped shape Finn’s career. Be it the literature critical to his shift away from private practice into the public sector or the books that have been pivotal in defining his career throughout both university and practice, some of which were discussed with Brian Eno in a conversation that Finn chaired for UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP). He is also a visiting professor of practice at IIPP, which is led by influential economist and author, Mariana Mazzucato, whose books Finn makes reference to throughout. With a broad range of interests and a varied career, Finn offers insights into a diverse and absorbing library that has been influential along this path. Enjoy...

How many books do you currently have in your office?

At Public Practice, I can’t even remember. The last time I set foot in our office was Mid-March last year, the week before the first lockdown started. We’ve got a library there of what I would call ‘grey literature’; the in-between publications that aren’t quite books, but aren’t just a PDF either. They sit in the world of policy, standards, and strategies. Grey literature has taken up an increasing amount of my reading bandwidth over the years. Some of these publications are produced by Public Practice. We just counted and I think we’ve published about 140 reports, resources and toolkits over the last couple of years with many more on the way.

My own books are here, at home. There are others dotted around the house, but this is where they are largely consolidated. They are a mix of books that I’ve collected over the years - and some that are still waiting to be read.

Are there any going with you when you initially move to Sweden?

That’s a good question. They’re all being shipped, but initially I’m taking books on Sweden, quite specifically those that relate to Malmö. I’m trying to read ‘Framtids Staden’’ by Lars Åberg at the moment. It is about how Malmö, partly because of its geographical location, projects the future for the rest of Sweden, for better or worse. Malmö is Sweden’s ‘front door’ - the way in which it opens up to the rest of the world. As a result it is exposed to trends and changes quicker than any other city in the country. Whether that is immigration, cultural diversity or shifts in the economy; Malmö has always been at the forefront of those changes. Åberg takes a complex and critical approach and is quite outspoken. It is interesting to read in the context of my new role. There are some other books here around Swedish democratic design, ‘Det svenska folkhemsbygget’ and its connection to the introduction of social democracy to Sweden in the 1930’s and the Stockholm Exhibition. For me, there is a close relationship between this idea of beautiful everyday design and what we’ve been trying to do through Public Practice.

“Malmö is Sweden’s ‘front door’ - the way in which it opens up to the rest of the world. As a result it is exposed to trends and changes quicker than any other city in the country. Whether that is immigration, cultural diversity or shifts in the economy; Malmö has always been at the forefront of those changes.”

Do you feel like that movement still lingers?

I think it is still there in Sweden and social democracy lives on in some form, but it is definitely challenged by more commercial attitudes and growing deregulation. This book has been useful for me, ‘Three Founding Texts of Modern Swedish Design’. The Acceptera movement in the 1930’s articulates a lot of what Public Practice stands for; valuing everyday places; getting the best designers to work for normal people.

“The Acceptera movement in the 1930’s articulates a lot of what Public Practice stands for; valuing everyday places; getting the best designers to work for normal people.”

Another book to come out of that movement is ‘Det svenska folkhemsbygget’ by Lisa Brunnström about Kooperativa Förbundets Arkitektkontor. The cooperative movement originated in England, places like Manchester and Glasgow, but it really established itself powerfully in Sweden in the late 1800’s. This was initially through food, but it grew into other forms of commerce. From 1925 onwards, a group of leading architects in Sweden got together and decided to form a cooperative architecture office - to place the best design in the service of the most ordinary buildings. They built beautiful factories, schools, corner shops - completely normal, everyday buildings.

Yes, but the cornerstone of communities.

Exactly. They were designed in an anonymous way, but incredibly well. This office, called KF for short in Swedish, was an important influence on Public Practice - the idea of gathering together, not just architects, but all kinds of brilliantly talented experts and placing them in the public sector, to design our everyday environment.

The fact there is a cooperative underlying that movement is compelling; this idea that individuals can gain knowledge through interaction, but then bring that back to the cooperative. As you say, similar to the role that research and development plays at Public Practice - developing a knowledge basis across different people and boroughs. It fills a role that central government can’t, or at least is refusing to do. A fascinating idea and model for how you interact with the public.

It is also something that I have been thinking about as I move away from working with a network of practitioners, to working as a city architect. In many ways it is an old fashioned idea; that the power and vision to shape a city’s future should be held by one person. It is definitely going to be a challenge for me, as it is quite against my own instincts. Instead of just working as a city architect, I want to work on turning Malmö into a city of architects, where those living in the city feel like they have a meaningful influence over their public realm and environment.

“After nearly four years of Public Practice, I have 177 Associates to learn from. Hopefully I’ll be able to take what I’ve learnt from each of those Associates and draw on that experience over the next few years as I go through the same process that they have been through. It’s not going to be easy in a different system, a different city, a different language and a different country, but it is a fantastic opportunity.”

And presumably alongside this reading on Malmö and the history of social democracy, there is a large proportion of guidance and legislation that you are having to get your head around?

Yes, that’s where the grey literature comes in again! There are a number of ambitious documents led by the government at national level around architecture and design, including ‘Politik för gestaltad livsmiljö’. It was driven by Malmö’s former City Architect and Executive Director for Place, Christer Larsson. He is one of the key figures behind Malmö’s progressive attitude to urban planning and sustainability over the last 20 years, and he went on to develop a national architecture policy - a policy for a designed everyday environment. It is a very ambitious, high-level and wide-reaching statement of intent from a national government, but I think it’s fair to say there are few places that have put it into practice. I want to show how it can be translated onto the ground in Malmö.

Amazing. There’s a very subtle nuance to that, whereby your role in the UK has often been pushing government, local councils and policy-makers to make policy more ambitious. Now, you’ve already got the ambitious policy in place and it is your role to try and implement that. I can imagine that is going to be quite difficult.

Most definitely. But, after nearly four years of Public Practice, I have 177 Associates to learn from. All of these Associates are doing incredible work to get their head around their organisation, to drive change and to mobilise and encourage colleagues. Hopefully I’ll be able to take what I’ve learnt from each of those Associates and draw on that experience over the next few years as I go through the same process that they have been through. It’s not going to be easy in a different system, a different city, a different language and a different country, but it is a fantastic opportunity.

It will be an amazing experience. It will be intriguing to see how the literature you’ve touched upon here and obviously developed an interest in will influence that practice. Have the bookshelves been ordered in any way to help you bring together certain books?

I wish there was, but sadly not. I would love to organise them, say by colour, but with children on hand to constantly pull stuff out, it’s not going to happen. The nature of the bookshelves means they are organised by size, purely pragmatically. Then there is normally a pile of books that I’ve been meaning to read that I’ve just bought or been given; sitting on the table and making me feel guilty.

“My interest in the public sector was really sparked by the experience of meeting passionate, humble, committed, yet relatively anonymous officers whilst working on private sector projects. They really impressed me and made me realise how much influence you could have from within planning departments. Once I moved, a few key people and their books have helped me to become more ambitious about what the public sector can be.”

You started in private practice and slowly made your way into the public sector, was there any literature that was particularly influential in that journey?

I don’t think there was one book that I could point to. My interest in the public sector was really sparked by the experience of meeting passionate, humble, committed, yet relatively anonymous officers whilst working on private sector projects. They really impressed me and made me realise how much influence you could have from within planning departments. Once I moved, a few key people and their books have helped me to become more ambitious about what the public sector can be. In the early days, while working at Croydon, one of those was ‘Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary’ by Dan Hill. A good friend of mine, Dan has helped me generate ideas, energy and enthusiasm. This book that he wrote during his time at Sitra in the Helsinki Design Lab is a brilliant exploration of how you can design strategically within public sector organisations and systems.

The other book, published around the same time was ‘The Entrepreneurial State’ by Mariana Mazzucato. Dan and I are both visiting professors at the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose that Mariana runs at UCL. She has helped build a significant movement of new thinking and ambition around what the public sector can do. ‘The Entrepreneurial State’ was the first book that really expressed the level of ambition that I felt should be there. Despite coming from an economist, it felt like the closest piece of literature that I had read to what I was trying to do in the built environment.

Another interesting book to put in that mix is ‘Seeing like a State’ by James C. Scott. I wouldn’t say it was a driver for me going into the public sector, but it helped me challenge a lot of my own preconceptions about the role of the state. Scott shows what can go wrong if communities and places are led by an overly modernist system of state-led control through seven distinct stories. One chapter discusses the management of artificial, monocultural forestries, and how a seemingly efficient process can destroy ecosystems over the longer-term. It is an incredible allegory on the risk of over-control and top-down management, mistakenly trying to make everything conform to one system. It really stuck with me.

Its application to the built environment in that sense is very interesting and the devastating impact we as humans are having on the natural world, but also as a metaphor for the way in which we control things and the effect that can have on humans as sentient beings.

Exactly, in that sense it completely relates to society at large. You can read many of the examples in that book and be reminded of modernist planning. A lot of social progress was made between the 1950’s and 70’s, but you can’t turn a blind eye to the damaging consequences for communities that often resulted from a one-dimensional way of thinking about the city. This book is powerful reminder not to try to control everything.

“Passages in the book are both inspiring and terrifying. Inspiring in the way he makes things happen; the incredible resourcefulness, pragmatism and masterful politics. But at the same time, a deeply terrifying warning about what happens when the public sector oversteps itself and becomes unaccountable to normal people.”

Another book that does that, which has been one of the most influential books for me, is ‘The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York’’ by Robert Caro. It is an almost real-time account of Robert Moses’ 30 years as the most powerful man in New York’s built environment; from his beginnings, advocating for reform of planning, law and social policy; to creating an incredible network of parks and open spaces; to him generating a power stranglehold over all built infrastructure projects in New York, trampling over ecosystems and communities. He ultimately gets locked in battle with people like Jane Jacobs, who was of course opposed to this top-down, highly-controlled, highly-engineered approach to re-structuring the city. Passages in the book are both inspiring and terrifying. Inspiring in the way he makes things happen; the incredible resourcefulness, pragmatism and masterful politics. But at the same time, a deeply terrifying warning about what happens when the public sector oversteps itself and becomes unaccountable to normal people. It is an amazing multi-dimensional book which would make a brilliant long-form TV series. I think it could be a worthy successor to ‘The Wire’.

Now that you have segued into public practice and are operating less as an architect, are you looking at many architecture books?

To be honest, I’ve probably always been more interested in books about non-architecture. An important book for me is Stewart Brand’s classic, ‘How Buildings Learn’. My copy is well thumbed. There’s a radicality to Brand’s thinking, particularly on time, which has been an interest I’ve retained throughout my career, specifically the idea of the long-term. It is a critical dimension of practice, especially when talking about sustainability. This book introduced me to a certain kind of thinking; that a project is not finished at practical completion, but rather, it is only just beginning. It challenges the traditional role of the architect, discussing many places and buildings that we love, explaining that they are often not conceived in a split second of architectural genius, but rather have come about through a slow process of use, re-use and adaptation. That’s what amazes me about cities. It is a critical book for architects to read as I think many are still stuck in a model of practice that is more about users adapting to architecture than architecture adapting to users.

I found that really interesting in your discussion with Brian Eno - the collective conversation in making buildings and the difference between architecture and urbanism that you just alluded to; architects want to control everything, whilst urbanists don’t, and can’t. How do you manage that as a planner when all of these architects are trying to do their own thing…

Many architects will say that their ultimate client is the public. But, if you’re working for the public sector, your client really is the public. You are serving them; you are paid directly by them; you are accountable to them through democratic systems - that is who you have to listen to. I think that in itself forces you to have a different relationship to diverse and contradictory voices, which is for me, what makes the process of urbanism more complex, challenging and interesting. It’s not just about finding the perfect solution to one client’s brief. There’s no such thing as one client in the public sector.

I was reading your interview with Pooja Agrawal for Foreground and was blown away by the discussion on the role of someone in the public sector interviewing people at a train station. Suddenly, when money isn’t the most valuable thing, hearing people’s views and voices, and being able to create places according to those voices, becomes paramount. I work in private practice and it can often feel the complete opposite of this.

Most definitely but it is not that commercial concerns are completely absent from the public sector. Austerity was – and continues to be – a particularly tough period. But the public sector is a rare form of institution that can afford to think genuinely long term for a genuinely broad range of people. Not many parts of the built environment industry can do that.

Is there anything that you would recommend to those in private practice that they read? Or perhaps that you would give to a private client to think more broadly? To think in terms of the city, its people and a wider public?

It is a very good question and maybe it’s a book that needs to be written. There are plenty of books looking backwards, to show how it has been done historically. It is interesting to see that there’s been a new wave of those books recently, ‘Municipal Dreams’, ‘Cook’s Camden’, ‘Red Metropolis’, ‘Concretopia’ and so on... But they are about a different time and show the results of amazing levels of ambition; what the public sector was able to achieve.

It is interesting to think about that era as well as showcasing high levels of ambition. Undoubtedly incredible buildings, but I think as architects we can have an obsession with Brutalist buildings, but for a wider audience they can often feel oppressive, quite disconnected from when they were built and the huge social change that you touched upon earlier.

I think you are right. It’s easy for architects to festishise those aesthetics, but harder to figure out how to bridge the gulf in political contexts compared to today. One book I would suggest if you were trying to convince a client is Mariana Mazzucato’s book, ‘Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism’. If a client is economically driven, but is also interested in what broader social value they can create, then they should find this book informative. It tackles the major challenges that we face as a society, whether it’s the climate, or COVID, all linked to the role of the public sector.

‘Lived-In Architecture’ by Philippe Boudon is an interesting book in relation to ‘How Buildings Learn’. It is a sociological study of Le Corbusier’s Pessac in Bordeaux. It is in the TV series actually. This sociologist spent years studying Pessac, recording all of the changes local residents made to the archetypal Corbusian house including adding pitched roofs, changing the ribbon windows, putting on strange terraces, or adding bizarre fancy fences outside. These are all Corbusian villas that have been turned into vernacular buildings. I visited them and was devastated to find that they’ve been largely restored back to their original forms. It’s both an entertaining and serious sociological study about why people change modern architecture and how that reflects the way they live.

It poses multiple questions about who you are making architecture for, and why?

Completely. It was also an influence for me and David Knight when we collaborated on the exhibition ‘The Rule of Regulations’ for the Architecture Foundation and the Berlage, and the publication ‘SUB-PLAN.’

And having just seen a note here on the page, you’re definitely annotating books?

Some more than others. I usually add bookmarks, but nowadays I keep notes on my phone. As much as I like opening a book and spotting an annotation, notes on a phone are a lot quicker to locate.

And is this informative way of reading feeding into your practice at all? With Public Practice or elsewhere?

It is for talking, writing, teaching...I write down quotes or ideas when I want them to sink in further. I’m the kind of person who makes constant notes in meetings, not because I need them for the record but because writing helps me process information. It’s the same with books, if I want it to stick I have to write it down.

And where are you finding the books you collect?

At Public Practice we ask each Associate to recommend one book that they would recommend to future Associates - something that has been influential for them. I always had a dream of turning that into a real, physical library – which in theory by now would have 177 books. Unfortunately we’ve never quite realised it in that form, but we have kept a record of all the recommended books. That has been a great resource for me as we have had such an amazing range of people coming through the programme, with much broader frames of reference than I have ever had. They’ve recommended some books that have become important to me.

One of those books was ‘Poverty Safari’ by Darren McGarvey, a really clever book with an audacious structure – which it turned out I had a personal link to. Embarrassingly, when I was studying at the Macintosh in Glasgow, I co-founded a hip hop group and label. We started a club night and an open mic session and it started to gather a bit of traction. There were a couple of people in the group who were really talented. Sadly, I wasn’t one of them! The moment when it really took off, and made me realise that I wasn’t cut out to do hip hop, was when we did an open mic session and this kid came up on stage; short, ginger hair, white shell suit. He was younger than me and I don’t know if he’d ever been on stage before but the raw emotion and power that came out of him blew everyone away. He didn’t comply with any of the traditional hip hop rules that we were dutifully following. He just exploded, talking about his background, his Mum, his estate. It taught me what hip hop is really about. That was Darren McGarvey. He ended up becoming a big rapper, and a big voice on the kind of social exclusion that I will be trying to tackle in Malmö. I didn’t make the connection at all until I read the book. It’s an inspiration for the kind of work I want to be doing in Malmö, where as Swedish cities go, there’s a lot of social segregation and inequality.

“It describes with incredible detail what the place is like, without ever really describing the architecture. It is probably the deepest and richest sense of a place I’ve ever got from a book, told through the voices of the people that live in it.”

If you could re-discover one book, what would it be?

I’m glad you asked that question, because it gives me the chance to talk about this, ‘The People of Providence’ by oral historian Tony Parker. He spent a few years living in a housing estate in, I think, Southwark, speaking in depth to all of his neighbours. Each chapter is written from one of their perspectives. As you read the book, you get personal stories of their history, their worries, their hopes – which start to overlap and weave together to build a complex and sophisticated picture of the community in this estate. It describes with incredible detail what the place is like, without ever really describing the architecture. It is probably the deepest and richest sense of a place I’ve ever got from a book, told through the voices of the people that live in it. It is something that Georges Perec attempted to do as a work of fiction in ‘Life: A User's Manual’. But this is the real thing - Tony Parker, just listening to people. As an oral historian he removes his own voice, but by the end you are left with this reverse impression of what he must have been like to have been able to have these conversations, incredibly open and generous, interested and thoughtful. It taught me the power of asking the right questions. I’m the kind of person who wants to jump to an answer; to fill in the gap if there’s a pause in the conversation. You start to realise the power and the wisdom of people like Tony Parker, of asking a good question and then listening and recording it - a much more powerful way of understanding people and places. Since then I’ve bought a number of his other books, but that’s the one that made the biggest impression on me. Incredible.

Finally, a book that you would recommend every young aspiring architect to read?

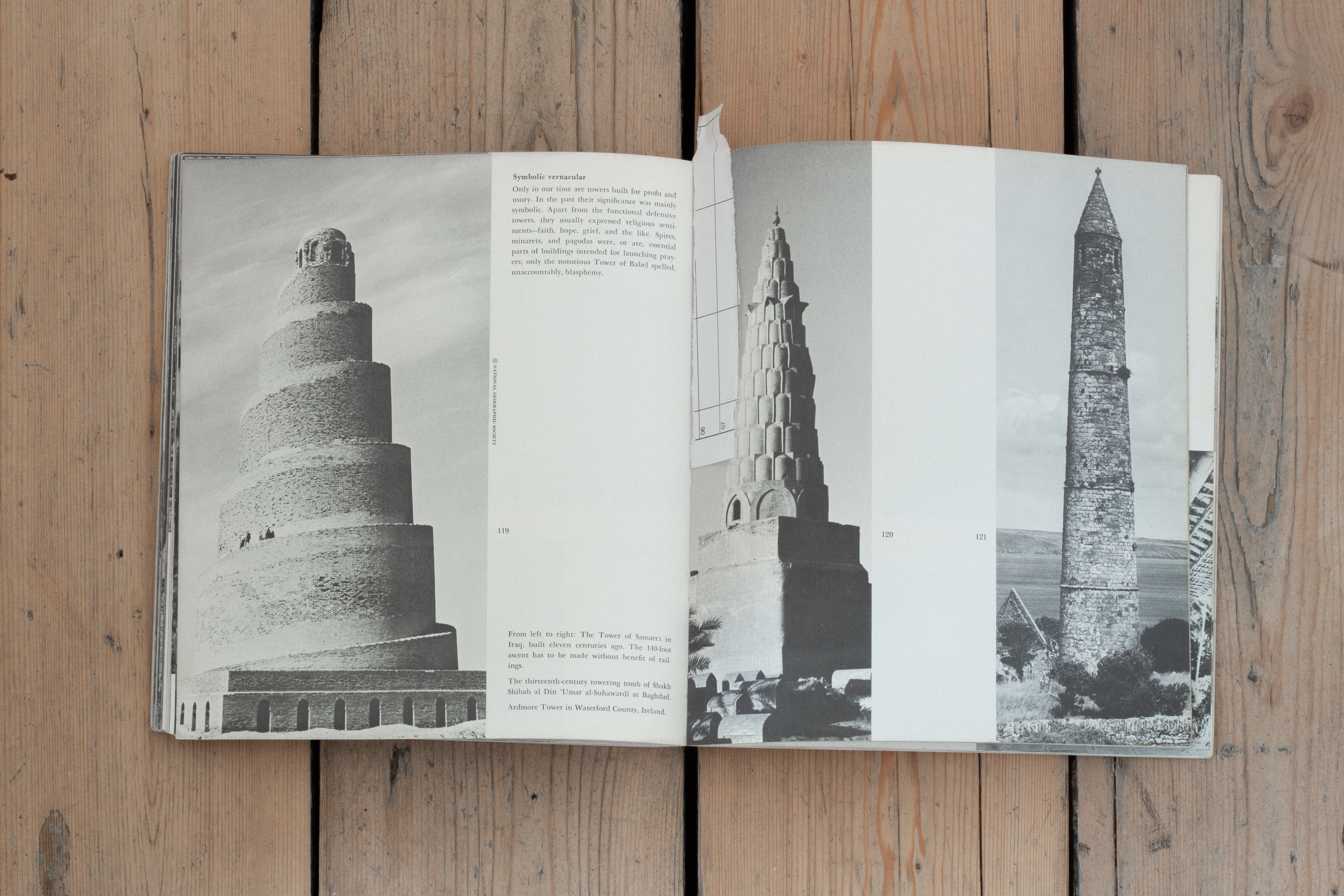

Aside from ‘How Buildings Learn’ by Stewart Brand I’d suggest another classic, Bernard Rudofsky’s ‘Architecture without Architects’ – as an antidote to every architectural monograph ever published. One thing I’ve always wanted to do is pinpoint each of these places on a map and then gradually visit them in my lifetime, if they are still surviving. I’d also like to do an updated version. What does architecture without architects look in the 21st century?

One of the beautiful elements of this book is that I can imagine that many of the people who created these buildings wouldn't expect them to be still standing. They are largely built from the earth, and in that way designed to go back to the earth.

All of these buildings have such a direct relationship to the place they are from; literally from the ground up. Luckily I’ve managed to visit a few of them. My Dad actually showed me this book when I was 6 or 7. This may even be his copy. He wasn’t particularly interested in architecture, but it was one of those books we had around the house that caught my imagination.

Preparing for this interview has made me realise that a lot of the books I’m drawn to are urban books; books that are complex, with multiple characters, different perspectives, and no single, linear narrative. That has always been the literature I’ve enjoyed reading, whether it’s ‘Nostromo’ by Joseph Conrad, or heavy-hitting Russian classics like ‘War and Peace’ by Tolstoy. They are urban books in the sense that they build a world and a city of characters, they populate it and see how it plays out. I think that is why I also love ‘The Wire’. There is no single narrative; no clear lead character; no obvious good or bad side. It is just how we understand a place, through the diverse perspectives of the various people that inhabit it. Perhaps that also partly explains why I’ve moved away from practising as an architect – the equivalent of the novel with the single heroic protagonist – to becoming more of a planner – where stories can be written and read in different ways.

All photography by Tim Lucas unless otherwise stated.